In the manifold and often ugly ways people interrelate with animals, Bewick’s wood engravings portray the specifics of rural northern England at a time when conditions, politics and views toward the land and nature were changing (urbanization, privatization of land, and the disappearance of the commons). Bewick escapes nostalgia, although many of his tiny, delicate engravings are pastoral and sweet.

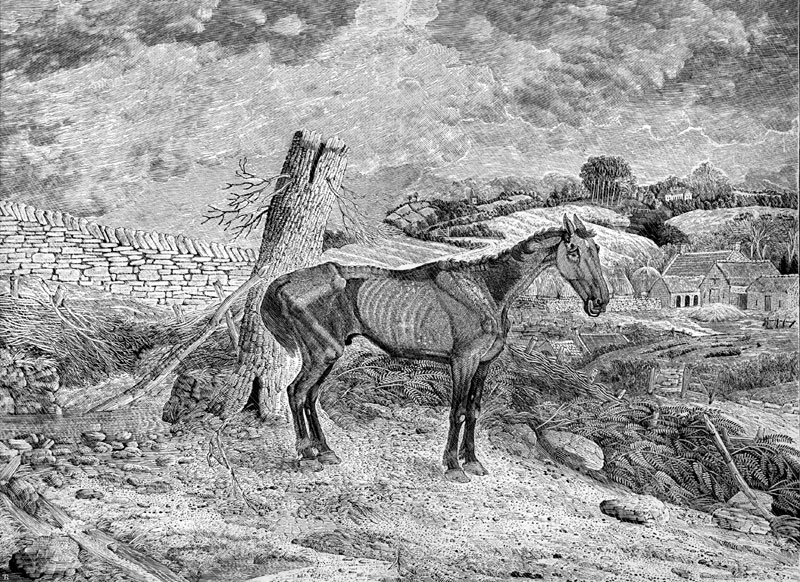

But at times Bewick makes an overt (and dear) statement of injustice. I found this image and decription on the Bewick Society web site :

This single sheet print (8 3/4 x 11 1/2 inches) was the last piece Bewick worked on before he died. It was part of his experimentation in larger sized prints and it was not finished when Bewick died. It was published by his son Robert Elliott Bewick in 1832. The subject matter was identical to a much earlier vignette-sized print based on one of his earliest known drawings

[From the descriptive text written by Bewick to accompany the print Waiting for Death. The full text is in Robert Robinson, Thomas Bewick: His Life and Times, p. 163-4.]

In the morning of his days he was handsome – sleek as a raven, sprightly and spirited, and was then much caressed and happy. […] It was once his hard lot to fall into the hands of Skinflint, a horse-keeper – an authorised wholesale and retail dealer in cruelty – who employed him alternately, but closely, as a hack, both in the chaise and for the saddle; for when the traces and trappings used in the former had peeled the skin from off his breast, shoulders, and sides, he was then, as his back was whole, thought fit for the latter […] He was always, late and early, made ready for action – he was never allowed to rest.[…] It is amazing to think upon the vicissitudes of his life. […] But his days and nights of misery are now drawing to an end; so that, after having faithfully dedicated the whole of his powers and his time to the service of unfeeling man, he is at last turned out, unsheltered and unprotected, to starve of hunger and of cold.

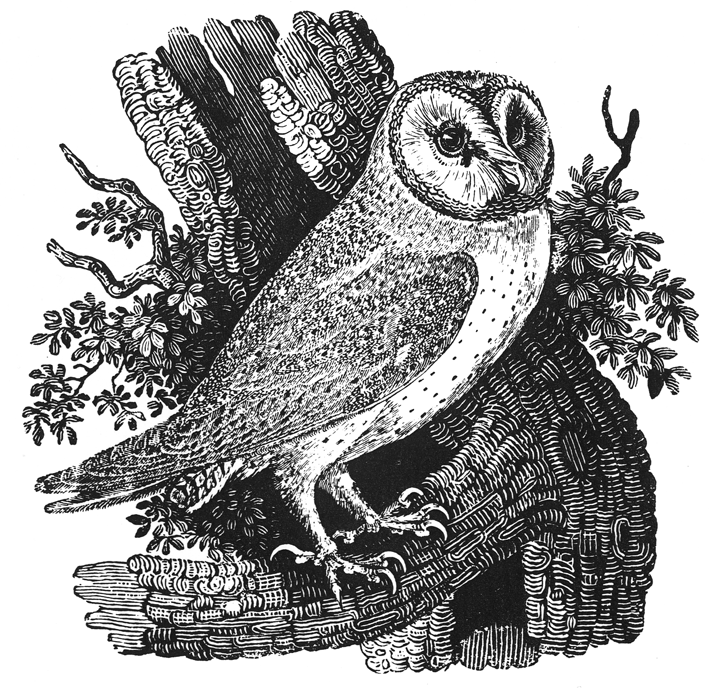

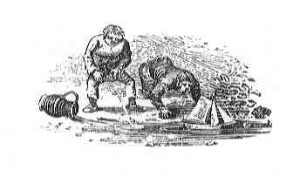

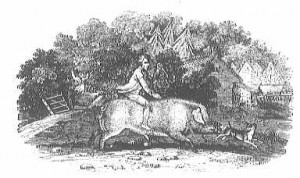

His tail-pieces – small vignettes made to fill space at the bottom of pages – form an anecdotal field guide to Northumberland life. His wry and tender view, and his sensitivity to relations – of species, of class, of the built and natural world – are fully apparent throughout his engravings. These are not great reproductions – the ones in Jenny Uglow’s biography, “Nature’s Engraver” are fantastic, and merit reading with a magnifying glass at the ready.

(tale-pieces from Tale-Pieces by Thomas Bewick)