Seeing Thomas Bewick preparatory drawings in the flesh at the archive today, with archivist June Holmes. Yes, I don’t get out enough and don those WHITE GLOVES.

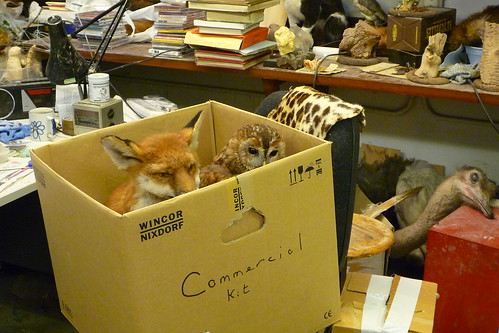

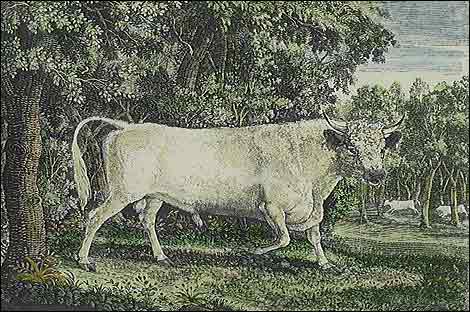

It was a thrill. Bewick’s work is astonishing – firstly, because of the level of detail at such a tiny scale, but also because he worked varying degrees of the detail into the drawings, which he transferred onto the blocks, and then did an enormous amount of the detail work on the block itself (in negative — did he see the world in reversed lines as well?). June Holmes said the animals he knew well just didn;t require that much preparation… roosters, dogs, local common birds, foxes…

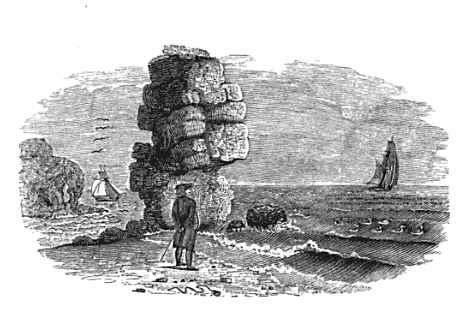

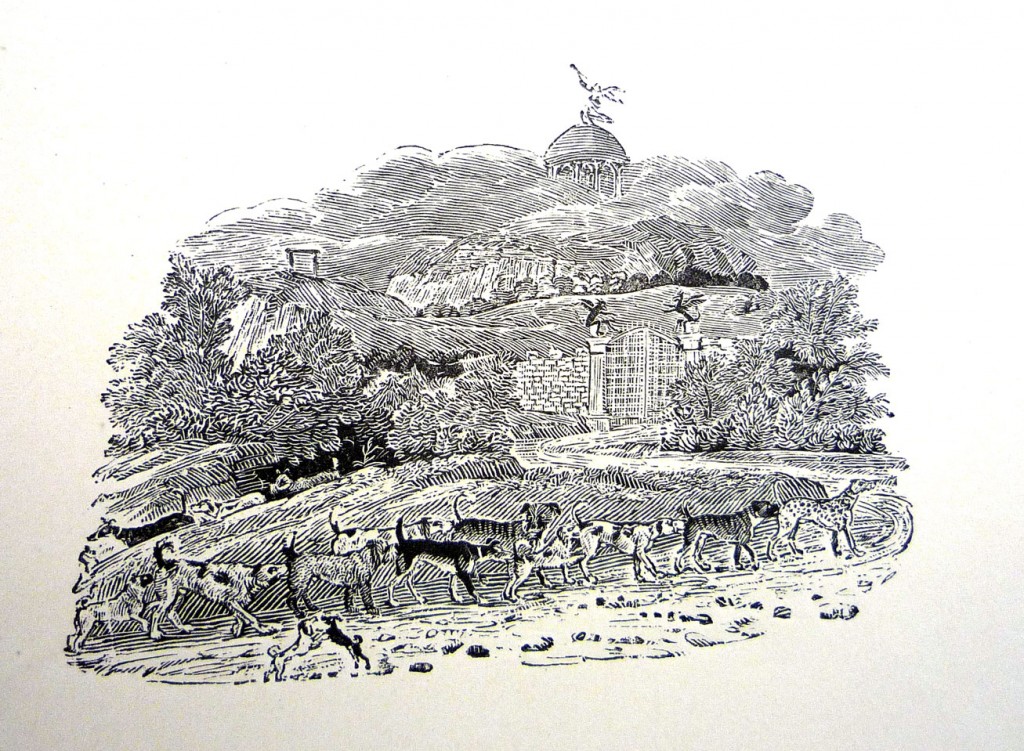

Here is an engraving that never got published.It is one of his allegorical/anecdotal “tail-pieces” – the original is about 3″ wide, max:

The Bewick Society has a lot of vignettes online – these were used as filler at the bottom of pages, but are far more than tailpieces- Bewick called them his tale-pieces, and they are worlds of their own, highly detailed miniatures that construct a natural history of everyday life, often with a memento mori quality. I’d always thought of his use of inscribed text upon the rocks as a way to illuminate the fact that the landscape itself is a kind of text, but apparently, he thought the landscape could become a site of morality, and he fancied to make it carry the word of God, so to speak (I think I’ll continue to believe in the “natural” texts of distinguished, dramatic landmarks, many of which have nicknames as wayfinding markers – synesthetic mnemonics in which being, place, and folkloric inscription tangle up to make geography).