This just in from Venue, an online mag produced by StudioX.

INVISIBLE FENCES: AN INTERVIEW WITH DEAN ANDERSON

(10 gallon) hats off to Studio-x for mixing urban and non-urban considerations of architecture.

I’ve been ruminating (yes) about how to better interface with and represent ecocritical investigations on remote public lands, and have the work BE more salient to an urban public.

I sometimes (often) get blank looks if I talk about the fact that we all own the USA’s public land.

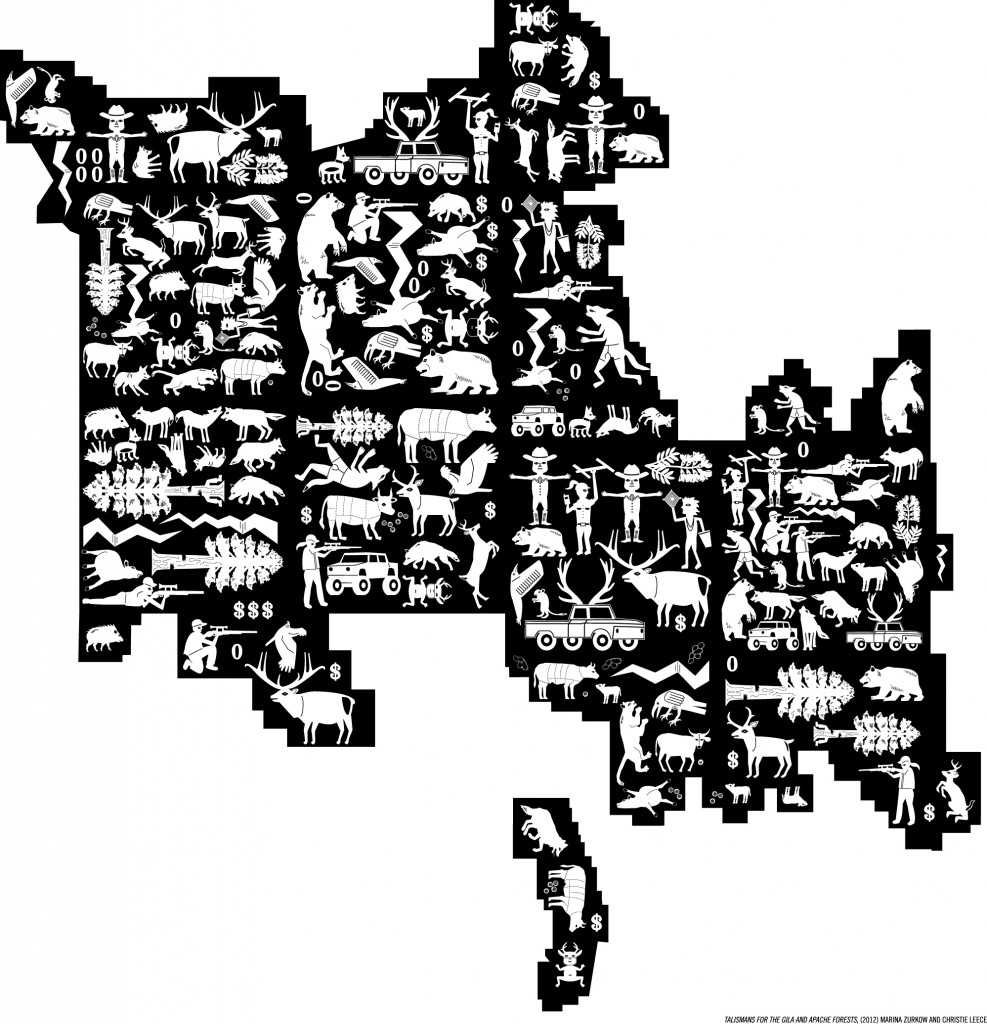

So much real and symbolic action takes place on this vast area (over 95,000 square miles) of high plains and high desert*.

In response to the interview about virtual fences, I’m thinking about

– at what point in the interview Anderson (and interviewer) mentions animal welfare – not until midway or later in article, certainly framed as secondary or even an after thought

– how easy it is to privilege convenience and human progress, continuing to make animal welfare second to your priorities (if that)

– looking at Anderson’s enthusiasm about technology controlling our literal actions (and not even in the future, right now, how that’s leading us)

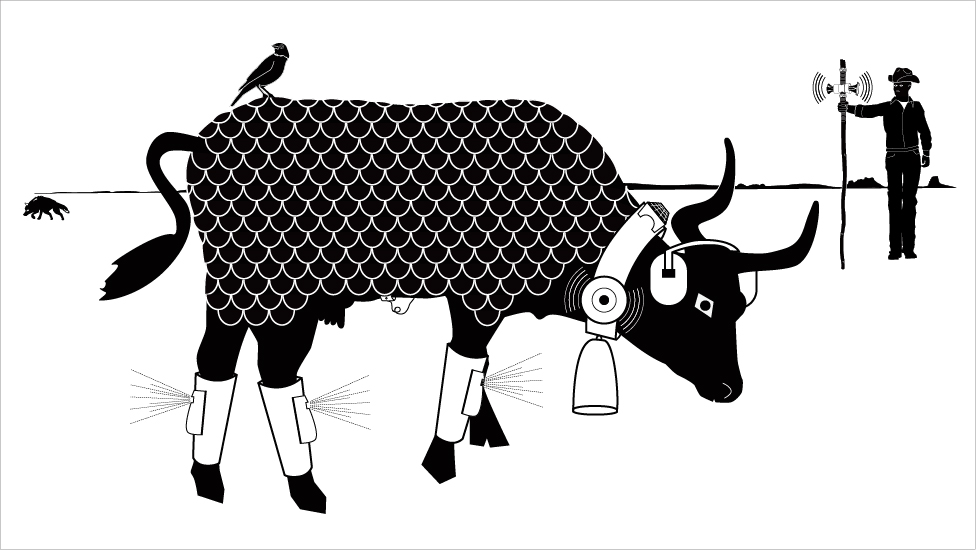

– cows are ‘handed’ (left and right) as we are. They can recall where virtual fences were (because they experienced unpleasant feedback to approaching theses zones)

– question: to surveille the animals via drones and electronics performs what in relation to control of human biopower?

– can one *really* fence off poisonous plants (a single one?)?

– can the drone birds be sent to frighten off wolves and lions and bears (oh my)?

– can songs be sung for other purposes across that landscape, like Anderson does in the cows’ ear pieces?

– the ‘new aesthetic’ privileges a remote sensing of the world, acknowledging the ever-decreasing direct apprehension we have or are interested in having (what are we doing with all that time we gain?)

– the ‘new aesthetic’ takes non-critical pleasure in surveillance, distance, and the production of accidental wonders. how does this operate with real animals (and real meat and money) at the end of the line?

– the positive impacts of the virtual fencing are great: ease of moving livestock away from riparian areas and depleted landscapes, away from predators, away from wild herds, removal of hard fencing helps wildlife’s mobility.

– remote sensing from drones (robo birds) can tell you a detailed story of the current conditions of the landscape:

Christie Leece (my collaborator on Gila 2.0) and I are trying to figure out next steps — hopefully in Arizona.

On a related note, basal ganglia controlled (like the robo rat in the Anderson article) in mice is featured on Radiolab:

Damn It, Basal Ganglia