One perspective:

CATTLE and WOLVES

Michael Robinson 2003

from Public Lands Ranching

…Cattle require huge quantities of water means they will always be vulnerable to wolves in the American West. For in this largely arid region, water and water-loving vegetation are so scarce, and scattered over such wide areas, that cattle must be similarly spread out, and that makes protecting them from wolves uneconomical; thus, as their forebears did, ranchers rely on federal agents to kill or remove wolves. Domestic sheep, much less numerous in the West than cattle, are even more vulnerable to predators, especially when flocks are not well protected. Thus, although wolves are a federally listed endangered species, their containment and control by the federal government constitutes one more subsidy that taxpayers provide the livestock industry in the West. (Some ranchers would no doubt happily dispense with this subsidy, as long as they were free to kill wolves at will, including putting out poison baits for them, as was common in the nineteenth century.)

The Southwest

In the Southwest, Mexican wolf reintroduction began in 1998, almost two decades after the last five individuals were removed from the wild for an emergency captive breeding program. The Mexican wolf, a separate subspecies from the gray wolf inhabiting regions to the north, originally roamed throughout Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, as well as northern Mexico. It, too, was extirpated from the United States by the federal government. Although the Mexican wolf is the most imperiled mammal in North America, it was designated “experimental, nonessential” like its kin in Idaho and the Yellowstone region, in an attempt to buy off livestock industry support for reintroduction.

It didn’t work. Soon after the first eleven wolves were released, five were shot, two disappeared, and the remainder were recaptured for their own protection. The livestock industry cheered the killings, and the New Mexico Farm Bureau and Cattle Growers Association filed suit to remove the wolves but were rebuffed in court.

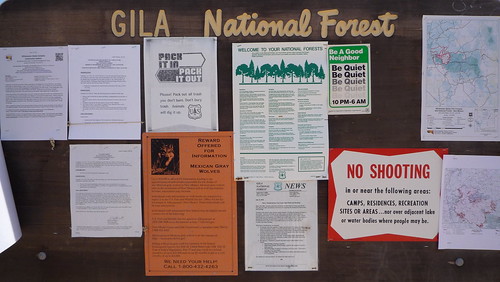

Over the next two years, government management of the Mexican wolves in conformance with their diminished protected status did even more damage than had the poachers. In 1999, the first released Mexican wolves to reproduce successfully in the wild were recaptured from the Apache National Forest in Arizona after they killed a couple of cows on national forest lands. In the course of that recapturing, three of the wild-born pups died from parvovirus. According to the veterinarian who necropsied them, the pups were already in the process of overcoming the disease at the time of capture, but the stress of that event likely caused them to succumb. After the survivors were rereleased into the Gila National Forest in New Mexico, two of the surviving pups dispersed from the pack at a younger age than is normal for wolves, and one is missing and presumed dead. Biologists do not know whether their period of captivity altered their behavior.

Another pack of Mexican wolves also preyed on cattle on the Apache National Forest, but in this case the cattle were illegally present, having been ordered out by the Forest Service because of severe overgrazing. There was so little forage present that deer and javelina had already been displaced. The rancher failed to remove his cattle, and Forest Service officials failed to enforce their own order-which they later rescinded. Meanwhile, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, unable to force the Forest Service to uphold its own decisions, managed to draw the wolves away to another (overgrazed) allotment on the Gila National Forest. But the wolves had become habituated to cattle, and a week after they discovered and scavenged on a dead cow in the Gila, they began killing cattle again. As a result, seven wolves were trapped, and one pup and a yearling disappeared; both likely died.

A third family of wolves didn’t kill livestock at all. But they were also recaptured after scavenging on a dead cow and horse left out on the forest. It was feared that the wolves might learn to prey on livestock after they had tasted beef. In the course of the government’s trapping effort, the adult female’s leg was injured in a leghold trap and had to be amputated. The pack was re-released into the Gila, but again, a previously tight family unit broke apart soon after. Two pups were subsequently trapped and returned to cages.

My observation is a little clumsy, but I think there’s something to it. These are grazing allotments. Nearly the entire Gila National Forest is leased to ranchers. These are HUGE allotments, where cattle are some times set to roam for months on end, drifting, eating, birthing calves. Actually, as I understand it, it’s even more complex: cow/calf pairs are released on range land, or entire groups of yearlings — one year old cows who get to spend a year eating grass before they are sold and transported to feed lots. The problem with these yearlings (as I understand it) is that they have no education in self-defense, and do not herd together (we saw many single cows or small groups widely dispersed). The cattle remind me of human adolescents, and much like American human animals, their humans would like a trouble-free environment to allow them to remain safe at all costs. We are a country that likes its comfort, and our sugar/alcohol/ritalin/ to normalize us and take the edge off. We are not alert as humans, so why would we want our livestock to be? I am making a distinction between alert and stressed out.

People complain about stress levels to the cows who, because of the wolf, now need to be ever vigilant. But even without the wolves, there were/are certainly bear and lion predations. Better husbandry practices or different breeds of cattle with horns and sharper herding instincts seem like a better idea than letting coddled complacent kids with no experience roam around in the wild alone. This is just my opinion based on observation here and in W. Texas, where I learned about people like Bud Williams and his stockmanship program. I was introduced to Ed Fredrickson, who was at UNM Las Cruces in the Agriculture Dept, and did extensive research on the Criollo cattle, a heritage breed from S. America who are small, tough, sharp-horned, and have good herding instincts. They are also accustomed to arid ecologies, and not as dependent on copious amounts of water, which is so precious and engineered in the desert. European breeds tend to need a lot of water, and hesitate to leave the bottom lands and flat stream sides, where they not only overgraze but also destroy riparian areas along the streams. This leads to unhealthy silty streams, and when the rains come, there is no vegetation to hold the debris back or stop the waters from becoming flood-threats.