Drawing is a way of knowing – that’s such an obvious statement but it’s true.

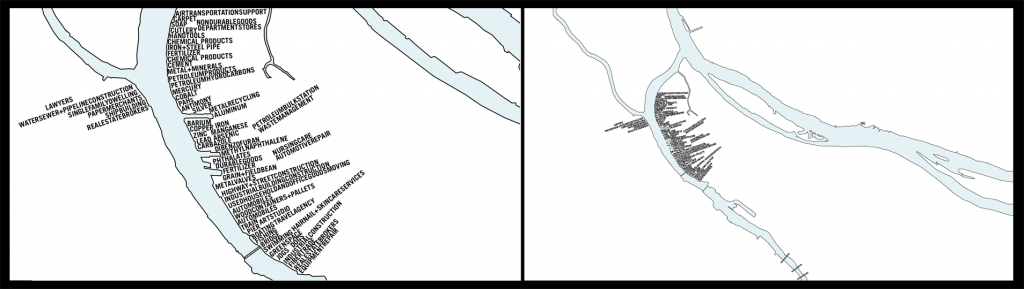

I started work on a way to visualize the Willamette and Columbia Rivers, flanking North Portland, the 11 mile superfund site and the startling fact that so many uses and agents (typologies, species, agendas, wants and wills, actions and reactions) are actually crowded together. I’m not at all certain of this method, but I am currently set on remaining agnostic to differences and placing no value or codification on the system as a whole. My methods include:

An accurate tracing from USGS topographic maps (just the river ways currently), which taught me a lot both through the intimacy of drawing the rivers – how the shore moves, how it got moved, where it got straightened and filled in by the USACE. You can see some older maps here. Drawing offers time and movement, and tracing offers freedom from too much interpretation.

I got some atlases from Portland’s Bureau of Planning and Sustainability (thanks to Sallie Edmunds) which were very helpful start points at understanding the various use-values of the shoreline.

To actually get tangible information (cars, chemicals, spa services, cement factories:

– Use the 2001 Willamette River Atlas to keep the whole picture in hand,

– Then go to google maps, where I can determine a shoreline address by using their “what’s here?” feature,

– Input that address into portlandmaps.com, navigating that rich interface (need to find prostitution? noise, garbage, hazards or elevation? This site can help you), to see what businesses are within a 1/2 mile radius of the spot I found. I hope I’m wrong and there’s a GIS database that lists all leaseholders as well as leasees, as many of the major real estate holdings are simply “Port of Portland” or “Toyota” and they rent out space. This also is a getting-to-know-you strategy.

-The shoreline can be further researched by going to the Oregon DEQ’s Land Quality Environmental Cleanup Site Information Database, and inputting some of the big land holders I found on the River Atlas, (like Schnitzer Steel) which is a goldmine (snort) of the perhaps less desired agents of influence like barium, lead, antimony, which have leached from prior practices.

I can sense how this map could obsess me – going through the sites is minor sleuth work, and although it’s exhausting, it has rhythm. Something(s) is missing though, which I look forward to unearthing.