“ranches with wolves” mother jones

There is a good article by Kiera Butler from April 2011 in Mother Jones, on the incompatibility of current dominant ranching practices in the SW with the wolves, and what ranchers might do to actually live in proximity to them. Arizona rancher Carey Dobson – his ranch is in the same contiguous Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area as the wolves being introduced in the Gila – is featured as a good example of the kinds of changes a rancher could make to reduce livestock predation.

Excerpt of article:

Dobson just wanted the wolves gone. But he reluctantly agreed to accompany Arizona biologist Chris Bagnoli to a workshop led by wolf-management experts in Montana, where ranchers and wolf defenders had begun working together. What Dobson learned there surprised him: Killing wolves that attack livestock doesn’t solve the problem. That’s because the offending animals have often passed along their knowledge. “You have to reduce the opportunities for wolves and livestock to interact,” Bagnoli explains. “That’s the only way to change pups’ behavior, since pups learn from adults.”

In 2007, Dobson and his wife began herding their livestock daily, and he installed electric fencing to keep wolves out. Although the wolf recovery program helped him with the details, the money came from two conservation groups: Defenders of Wildlife and the Mexican Wolf Fund. “Other cattle guys told me I was taking money from the devil,” says Dobson. “But you know what? It is really working.” With the new strategy, Dobson hasn’t had a single sheep kill, and only one calf has been taken. Bagnoli hopes that federal authorities will take note and improve programs to help ranchers give the humane methods a try.

Of course being willing to work with the Feds is an obstacle for many ranchers, who view the wolf as nothing but a Federal representative, and the tippy-peak of a mountain headed for a landslide, with regard to their own perceived land rights. On top of that, at least mountain lions have trophy value, and you are allowed to shoot coyote, bear or lion if they are predating your livestock. You are not allowed to shoot the wolves, and they are rather little besides, and don’t get those glamorous winter coats like their northern cousins.

Another excerpt:

On the surface, the ranchers seem to harbor undue anger over a few dozen limping lobos. But the wolves symbolize something bigger: a century-old debate over whether land is meant to be used by humans or preserved as wilderness. Roughly 170 ranchers live within the recovery area, many of them descended from pioneers who homesteaded the area in the 1800s. In 1905, Teddy Roosevelt declared the Gila a national forest, and the government took ownership. Today, the ranchers lease their land from the feds, and if they don’t follow the rules, they pay: Ranger caught your cow wallowing in the wrong part of the river? That’s a warning. Land looks overgrazed? Another warning—too many warnings, and you might lose your grazing permit. Most ranchers I spoke with said they feel harassed, even persecuted, by the government and environmental groups. “Their goal is to get us off the land,” a third-generation rancher named Hugh McKeen told me during an afternoon on his 11,000-acre spread. “The wolves are the last straw. They’re trying to get rid of us for good.”

You hear this a lot: The Feds are trying to remove the ranchers. Everyone is positioned in extremis: the same tropes are recycled with little variation. It seems to me that the patchwork of land that exists – what is private, what is public – really should change, meaning that everyone would have to participate in an enormous overhaul of a system of laws and usages that has been… well, patched together slowly and clumsily for over a century. Many people can’t trace their cowboy roots back to the homesteaded Territory days, but the myth and lifestyle (I have heard this word more here than in advertising and branding contexts) are such strong draws that it is very (hmm, easy? supple? tempting? self-justifying?) to don this mantle of historicity.

In addition, leasing and enforcement are not what they are on the books, the situations are far more complex than the article suggests.

And the wolf populations vary wildly from account to account: some say dozens, some say there are at least 50 uncollared wolves in addition to the 50 or so collared wolves in the Area. Some say the Feds undercount, in order to make their arguments. Many ranching advocates and even some environmentalists have complained about the Feds’ management.

In short – and I will absolutely repeat myself when I post about my last 4 days of traveling in the area – nothing is what it seems, and no one seems happy.

Climate change in the southwest

The Southwest, with its delicate desert ecology is even more susceptible to strain than other regions of the West. There are particular issues to the West that I am focused on: the intersections of ranching, wide open spaces, cowboy and freedom myths, concepts of wilderness, phenomena that encompass both acreage and lifestyle and are foundation to the image of America, but also some of our important resources including energy, ecology, and identity. I am witnessing all of these overlapping strains right now in the Gila: large scale fires; escalating tensions between ranchers and a variety of grassland and riparian conservation initiatives including any species protected under the Endangered Species Act; and of course, the motherlode issue which seems to contain all the others: wolf reintroduction vs cattle ranching.

There is a new (Dec 2011) book out by William deBuys: A Great Aridness: Climate Change and the Future of the American Southwest. deBuys posts about his book here. An excerpt:

“The news for the Southwest is not good: the droughts, fires, social strains and other stresses that lie ahead will challenge the region to the utmost. But the stories about how people came to understand those problems are endlessly fascinating, at least for me. In A Great Aridness I have tried to capture the “eureka moments” when the researchers I talked with glimpsed new and resonant insights – like when Tom Swetnam, who heads the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research at the University of Arizona, and Julio Betancourt of the USGS made the link between forest fire frequency and the El Nino/La Nina cycle. Or when Mark Varien of the Crow Canyon Archaeological Center found a great kiva at Sand Canyon Pueblo and was able to visualize in a completely new way the pueblo’s final days. Or when Chris Milly or Richard Seager, separately, realized that their climate models were telling them something big.

The surprise for me in writing the book was to come full circle back to issues I had been working on for many years. Yes, we urgently need to cut back on greenhouse gas emissions, which for virtually all of us means a radical change in the way we live. But we also need to take care of business that has long been unfinished, like living within a sustainable water budget and restoring fire resilience to our forests. Climate change only makes more urgent the big task that has always been before us: to learn how to live in the marvelous arid lands of this continent without further spoiling them. It is an old challenge. We have already had a lot of practice, and we should be better at it. We can be.”

In Dec 2011, The New York Times reviewed deBuys’ book and another book by Andrew Ross, Bird on Fire.

An excerpt:

“Dr. deBuys puts it somewhat differently. History teaches that people have difficulty adapting to prolonged, extreme drought, he writes. Faced with it, they typically abandon efforts to cope and simply abandon their homes. That is why we call dry places deserts — they are deserted.

Is that tactic likely for today’s Southwest? No. But, he writes, any answers to the water challenge will require “strong social will and collective commitment.”

At the moment, though, the region’s politics tend to embrace the idea that collective action of any kind is inherently suspicious or even evil; government is the problem, never the solution; and regulation is the bane of economic growth.

These ideas are not in accord with Dr. deBuys’s prescription, which is to “get on with what we should have been doing all along, including limiting greenhouse gases.”

There is no silver bullet, he writes. “There is only the age-old duty to extend kindness to other beings, to work together and with discipline on common challenges.”

Dot Earth post about the book

NY Times post about the book.

Follow up:

Ari Phillips’ 2012 research project, Energy and Climate Change in the American Southwest

Very funny. kind of.

“What is the world’s shortest book?

The environmentalist’s book of jokes.”

– from writer Sharman Apt Russell’s blog, Love of Place.

She continues in her post “The Lighter Side of Global Warming:”

“For myself, I also feel an intangible loss. Humans are wired for continuity. We believe in culture, tradition, grandkids. We believe we are connected to the future. In the twentieth century, where I spent most of my time, we even believed in progress. We were destined to move forward into something better. Now I feel cut off. Disconnected. The future is no place I want to go.

As Woody Allen wrote, ‘Mankind faces a crossroads. One path leads to despair and utter hopelessness, the other to extinction. Let us pray we choose correctly.'”

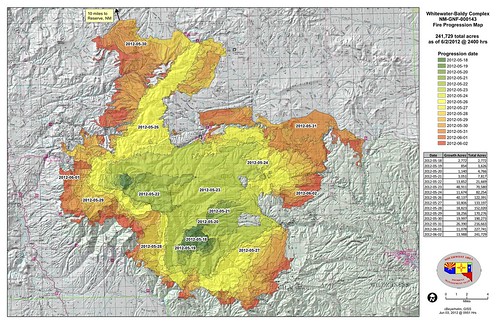

Forest fire

Against eliminating species

I just read this passage written by Harley Shaw, in the 2002 introduction for The Wolf in the Southwest, the Making of an Endangered Species (1983) by David E. Brown. Shaw is a research biologist specializing in mountain lions in SW NM:

“Eliminating species leads to intellectual dead ends. Once a creature is gone, we no longer have reason to understand it. Our world becomes simpler, and our minds simpler with it. Problem-solving is an open-ended activity. Interacting with a species provides a means for intellectual growth, eliminating it simply leaves another blank spot – on earth and in our minds.”