Sorry. I can’t stop myself. Here’s the best picture yet of a red squirrel. If ever there was a reason to protect the Reds, it’s their supersonic selfdom. Though this one looks wily enough to defeat the Pox.

ANIMALS, PEOPLE AND THOSE IN BETWEEN

Sorry. I can’t stop myself. Here’s the best picture yet of a red squirrel. If ever there was a reason to protect the Reds, it’s their supersonic selfdom. Though this one looks wily enough to defeat the Pox.

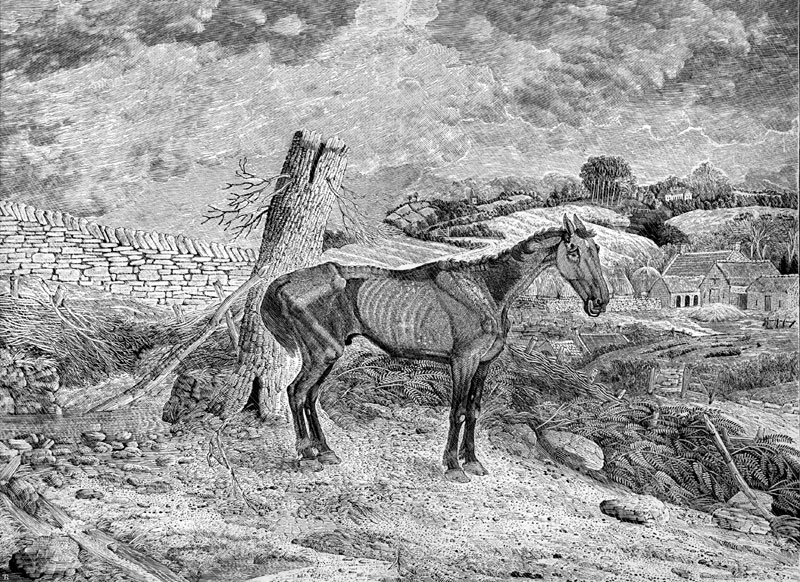

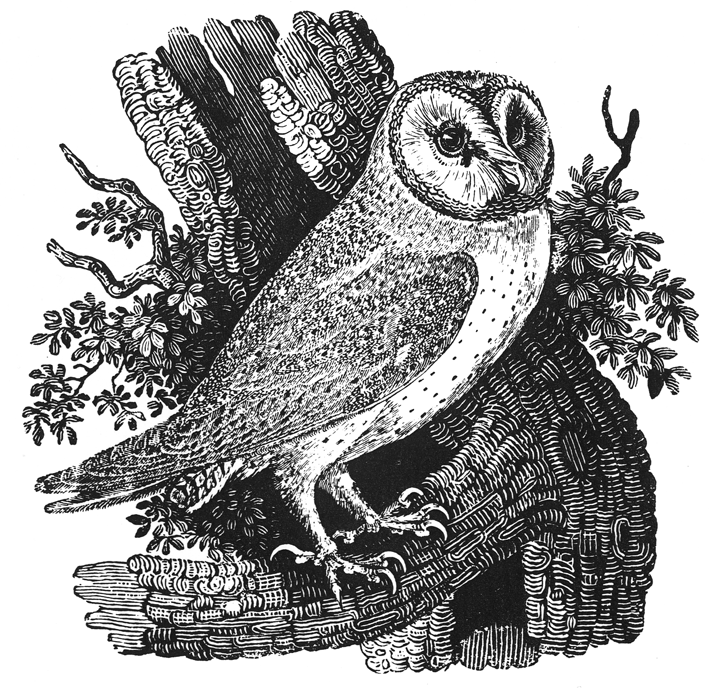

In the manifold and often ugly ways people interrelate with animals, Bewick’s wood engravings portray the specifics of rural northern England at a time when conditions, politics and views toward the land and nature were changing (urbanization, privatization of land, and the disappearance of the commons). Bewick escapes nostalgia, although many of his tiny, delicate engravings are pastoral and sweet.

But at times Bewick makes an overt (and dear) statement of injustice. I found this image and decription on the Bewick Society web site :

This single sheet print (8 3/4 x 11 1/2 inches) was the last piece Bewick worked on before he died. It was part of his experimentation in larger sized prints and it was not finished when Bewick died. It was published by his son Robert Elliott Bewick in 1832. The subject matter was identical to a much earlier vignette-sized print based on one of his earliest known drawings

[From the descriptive text written by Bewick to accompany the print Waiting for Death. The full text is in Robert Robinson, Thomas Bewick: His Life and Times, p. 163-4.]

In the morning of his days he was handsome – sleek as a raven, sprightly and spirited, and was then much caressed and happy. […] It was once his hard lot to fall into the hands of Skinflint, a horse-keeper – an authorised wholesale and retail dealer in cruelty – who employed him alternately, but closely, as a hack, both in the chaise and for the saddle; for when the traces and trappings used in the former had peeled the skin from off his breast, shoulders, and sides, he was then, as his back was whole, thought fit for the latter […] He was always, late and early, made ready for action – he was never allowed to rest.[…] It is amazing to think upon the vicissitudes of his life. […] But his days and nights of misery are now drawing to an end; so that, after having faithfully dedicated the whole of his powers and his time to the service of unfeeling man, he is at last turned out, unsheltered and unprotected, to starve of hunger and of cold.

His tail-pieces – small vignettes made to fill space at the bottom of pages – form an anecdotal field guide to Northumberland life. His wry and tender view, and his sensitivity to relations – of species, of class, of the built and natural world – are fully apparent throughout his engravings. These are not great reproductions – the ones in Jenny Uglow’s biography, “Nature’s Engraver” are fantastic, and merit reading with a magnifying glass at the ready.

(tale-pieces from Tale-Pieces by Thomas Bewick)

This in May 9, 2009, from the New York Times, courtesy Una Chaudhuri:

The history of animal escapes in New York City, collected in the archives of the city’s newspapers, reads like a feeding schedule at the Bronx Zoo — elephants, horses, wolves, bulls, monkeys, bears, goats, lions, deer and a six-foot boa constrictor named Minnie (captured in 1937 in Brooklyn)…

The tales of loose animals are odd little reminders of a lost era of the city, when there were monkey fanciers on the Lower East Side (loose monkey, July 1937) and when the site of the Hippodrome, now a sleek office building in Midtown with the same name, was home to a footloose elephant with a knack for the bass drum.

And this photo of Lucky Lady is from a 2007 escape in the Bronx, found in this article found on Associated Content.

The lamb was just 7 months old and was on an escape attempt from a nearby market where live animals are sold eventually ending up as food. This little lamb’s escape plan has worked and instead of her sad fate will now head to her new home in upstate New York where she will live on a sanctuary.

Well I’ll be; who knew?

The Royal Entomological Society, that’s who.

I am sad they only do even years – the next National Insect Week is in 2010

But they continue to host competitions like Close Encounters:

…and to offer loads of information on the National Insect Week web site.

There’s some great contextual material on insects as pollution indicators, on insect-friendly gardens, and on participating in insect surveys.

Seriously playful, and clearly in a long line of enthusiastic amateur naturalists. Here are some links –

The Royal Entomological Society hosts events, conferences, and publishes pamphlets + books like this one:

“A Year in the Lives of British Ladybirds,”

Iconically coloured, friends to farmers and gardeners alike, and named

after The Virgin Mary, Ladybirds are undoubtedly the most popular of all

the beetles…Written by three hugely experienced ‘ladybirders’, the book provides

instructions of how, when and where to find different species of ladybird,

how to identify the adults, and facilitates involvement in current research

projects on ladybirds. Excitingly, the book sets out ways in which readers

can contribute to national surveys of ladybirds, initiated as a result of the

recent arrival of the invasive alien harlequin ladybird in 2004.

This image freaks me out, as well it should.

from Wikipedia:

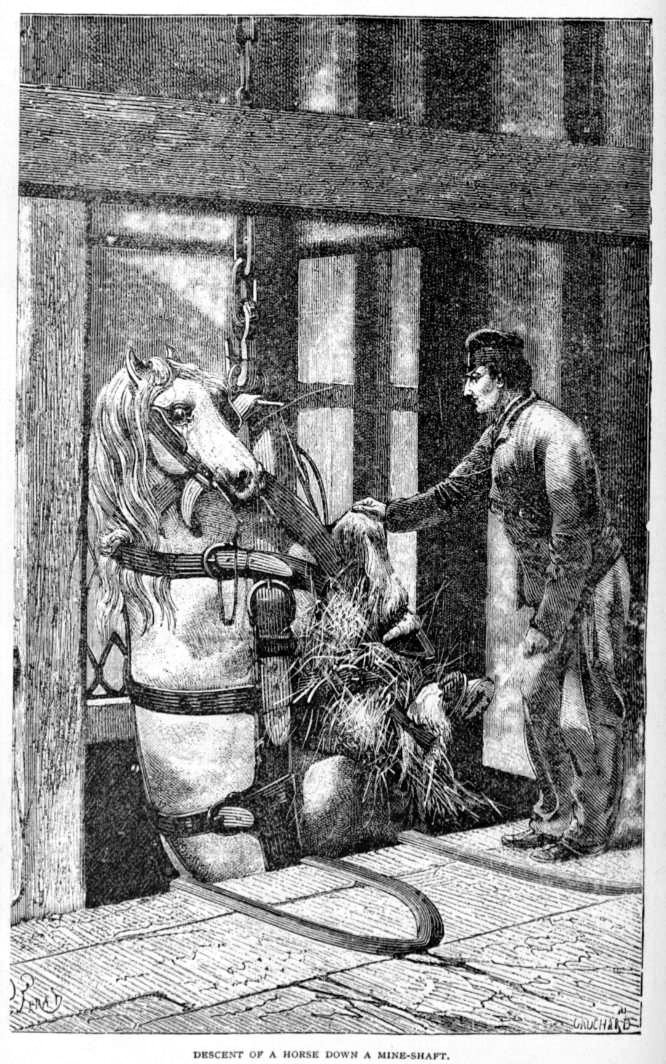

Ponies began to be used underground, often replacing child or female labour, as distances from pithead to coal face became greater. The first known recorded use in Britain was in the Durham coalfield in 1750. In later years, mechanical haulage was introduced on the main underground roads replacing the longer pony hauls (“driving”) and ponies tended to be confined to the shorter runs from coal face to main road (known in North East England as “putting”) which were more difficult to mechanise. As of 1984, 55 ponies were still at use with the National Coal Board in Britain, chiefly at the modern pit in Ellington, Northumberland. At the peak in 1913, there were 70,000 ponies underground in Britain.

From several of my superficial trawls, it is said that the ponies were well-looked after (better than the men), as they were a more difficult to replace capital commodity. In some cases, the stables even had electric lights, and they were given treats from the miner’s lunches, to coerce them to work harder. But in many cases, the ponies would remain underground for as long as a year.

The last surviving pit pony, Pip, died in February 2009 at the age of 35.

He worked at Blackburn Drift, Marley Hill Colliery, near Sunniside, Gateshead, and then at Sacriston Colliery, near Durham, and retired in 1985 when the mine closed. he spent his last 23 years at Beamish (open air museum). I bet he felt pretty happy and surprised about that turn of event. Telegraph, February 2009