A Swarm is My Bonnet was developed in 2017 as part of a residency supported by the Cape Cod Modern House Trust (CCMHT) and the National Park Service (NPS) that invites artists to work alongside NPS scientists in the field. Guest curators: Dylan Gauthier and Kendra Sullivan.

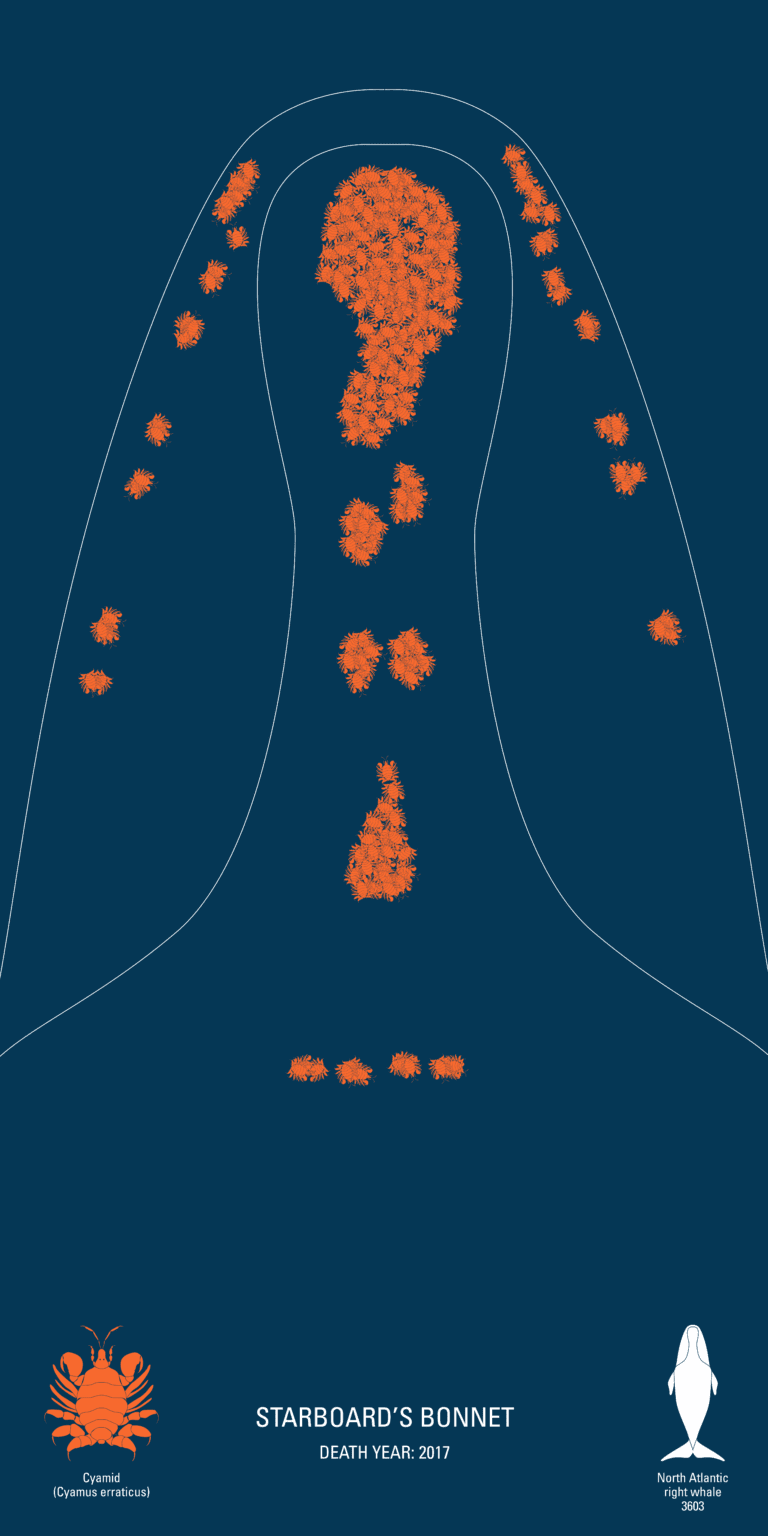

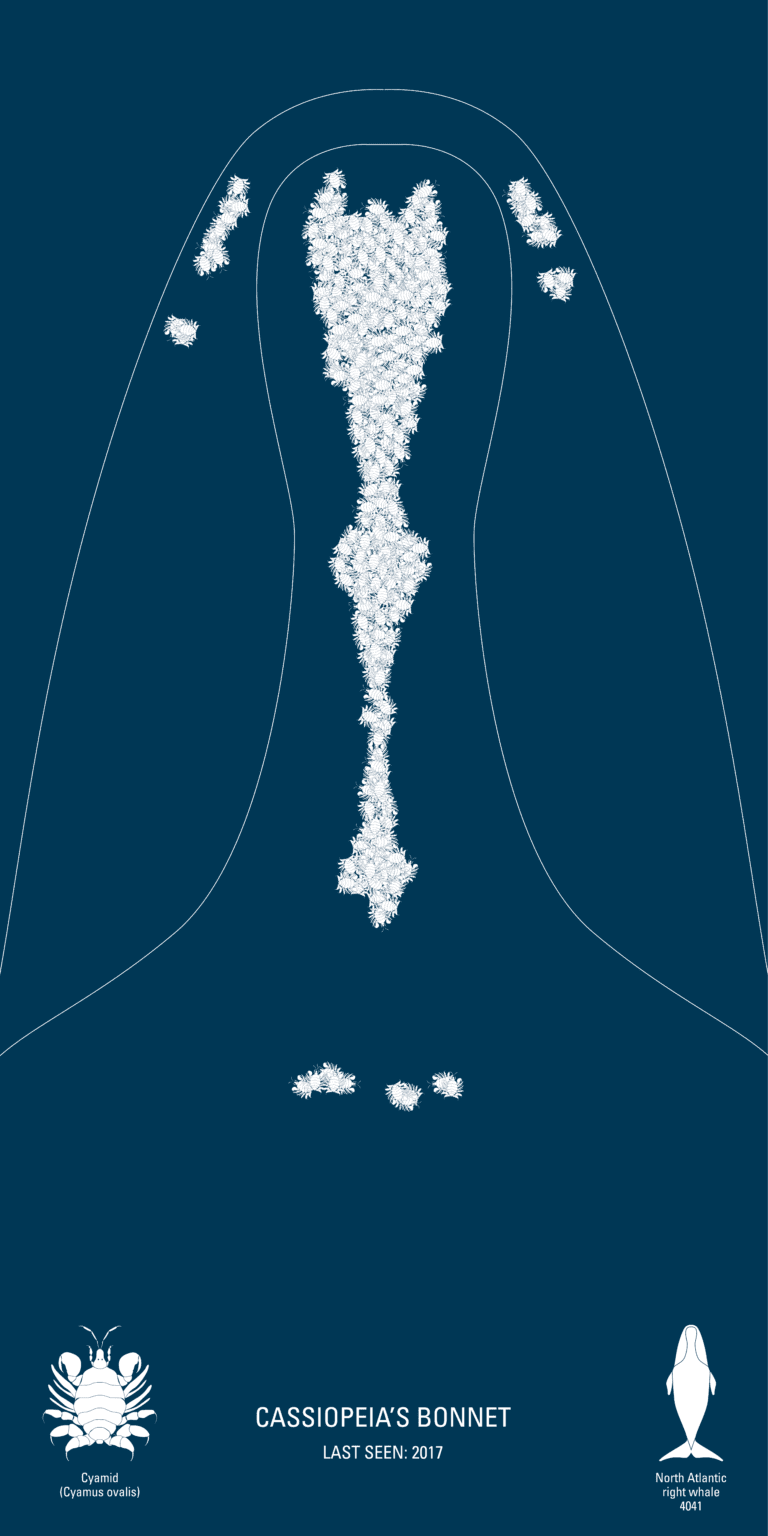

Right whale identification relies on the distinct pattern, known as a callosity, that each whale displays like a blazon on the back of their head. These are rough skin patches — callouses. Whalers called them “bonnets.” Each whale is born with their callous-formation, which grows pitted and grooved like volcanic terrain over time. Callosities would not be visible were it not for the species of cyamids who colonize them, eating algae and the whale’s sloughing outer skin. Whalers used to think these cyamids were lice, and the name stuck (“whale louse”) but they are actually amphipod crustaceans. These cyamids are white or yellowish, or orange, whereas the callosities are gray like the rest of the right whale. In effect, the cyamids allow us to uniquely identify each whale, which we do, from surveying airplanes. This identification is important to us humans, in order to track, quantify, characterize – and some might suggest care more about – the whales and their success or demise as a species. One could say the cyamids are producing signs that humans want to read. In fact, it’s a nuanced set of signs:

White bonnets – the whale is healthy.

Orange bonnets – the whale is ill, injured, or dying.

The poetry of this isn’t lost on anyone working in the field: cyamid species move around and relocate when the right whale is sick: C. erraticus move out of their genital folds and creases, and migrate into the wounds, signing Sickness.

On each right whale around 5000 Cyamus ovalis coat the callosities and give them their white color. In the spaces between the raised callosities live around 500 C. gracilis. On adult whales approximately 2000 C. erraticus live in the genital and mammary slits. C. erraticus is highly mobile though often occupying wounds, and living in large concentrations on the heads of young calves. Of these C. gracilis is the smallest with ~6mm long adults and with the other two species measuring ~12-15mm long as adults.

— http://other95.blogspot.com/2008/09/right-whale-lice.html

Cyamids spend all phases of their life cycle on their cetacean hosts. The cyamids who live on North Atlantic right whales know no other species or environment. They can’t swim. They are passed from whale to whale – for instance, from a mother to calf, or while mating.

After spending so much time thinking about, drawing, and positioning cyamids in their uniquely identifiable callosity patterns on right whale diagrams, I equally feel sadness for the loss of these tiny crustacea as for their enormous, charismatic hosts. When I browse the right whale catalog (from which I have been drawing), I see both an individually identified whale and its cyamid symbionts; when the whale data states “last seen” or “death year,” I experience the tensions between our capacity to care, to not care, to prefer nameable species, to shun the nameless or “uncharismatic” swarm. These cyamid portraits were uncomfortable to assemble. I could physically feel the otherness of the swarm as I assembled the bonnet groupings, for these are animals, and not simply signs.

These banners honor a colony of commensal animals who, coincidental to their lives on the whale, inadvertently “sign” the whale’s individuality to us human creatures. We who love both science and story tend to care more when we can identify individuals; the swarm of crustaceans, on the other hand, is grotesque because their form and their mass behavior is so alien to us. The cyamids perform a beautiful gift with their accidental labor of signing to us, helping us care about marine creatures who, ironically, are too large and submerged for humans to identify or interface with in any other way than through both the aid of tiny crustaceans and the distancing means of aerial photography.

I feel compassion for both right whale and C. ovalis, C. gracilis, and C. erraticus, whose numbers are declining, who all may very well disappear in our lifetimes from the earth (ocean), if we don’t significantly (there’s that word again, sign/significance) change our fishing and shipping practices that cause net entanglement, marine noise pollution, and ship-related injuries. Both right whales and their cyamid symbionts deserve to be honored and preserved, advocated for. Part of this advocacy is toward a change of mindset: find kinship with the horde, they who don’t speak, but who give us the whales’ names with which we quantify, identify (with), and defend.

Sources:

The individual bonnet portraits are drawn from the North Atlantic Right Whale Catalog (http://rwcatalog.neaq.org/), developed by researchers at the New England Aquarium for the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium

Encyclopedia of marine mammals. Würsig, B., Thewissen, J., & Kovacs, K. M. (2009, 2017). Elsevier Academic Press. “Epibionts” wikipedia

Right whale cyamid populations

Whale lice comparison

“Population histories of right whales (Cetacea: Eubalaena) inferred from mitochondrial sequence diversities and divergences of their whale lice (Amphipoda: Cyamus)”