The Invitation

You are invited to “Not an Artichoke, Nor from Jerusalem,” a dinner that renders the local exotic, and the exotic all too local.

We are serving a meal harvested in nearby waters or foraged on the adjoining shores. Tong-ho. Whores’ eggs. Knotweed. Sapidissima. Sumac. These words feel strangely potent in the mouth. Language frames our experience of food, and these names evoke rich and bloody histories that have identified them as food or as pest. And we promise: they taste very good.

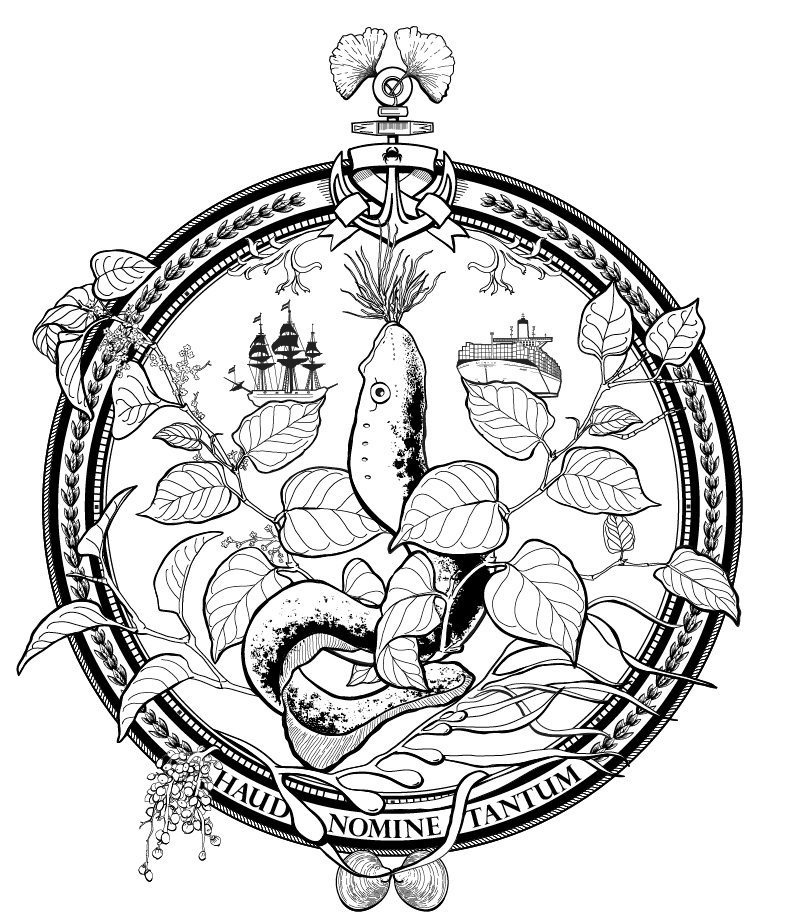

Some are native species that have populated the New York region for millennia, while others are invaders: species brought here as hitchhikers or once-welcome foreign guests. We shall feast Haud Nomine Tantum (not in name alone).

Please join us for a five-course meal, wine, special toasts, and cocktails, in an event conceived by the artist Marina Zurkow.

Monday, January 16th, 2012 7:30pm

The Artist’s Institute | New York.

Seating is limited to 25 people.Yours,

Michael Connor, Alex Freedman, and Marina Zurkow

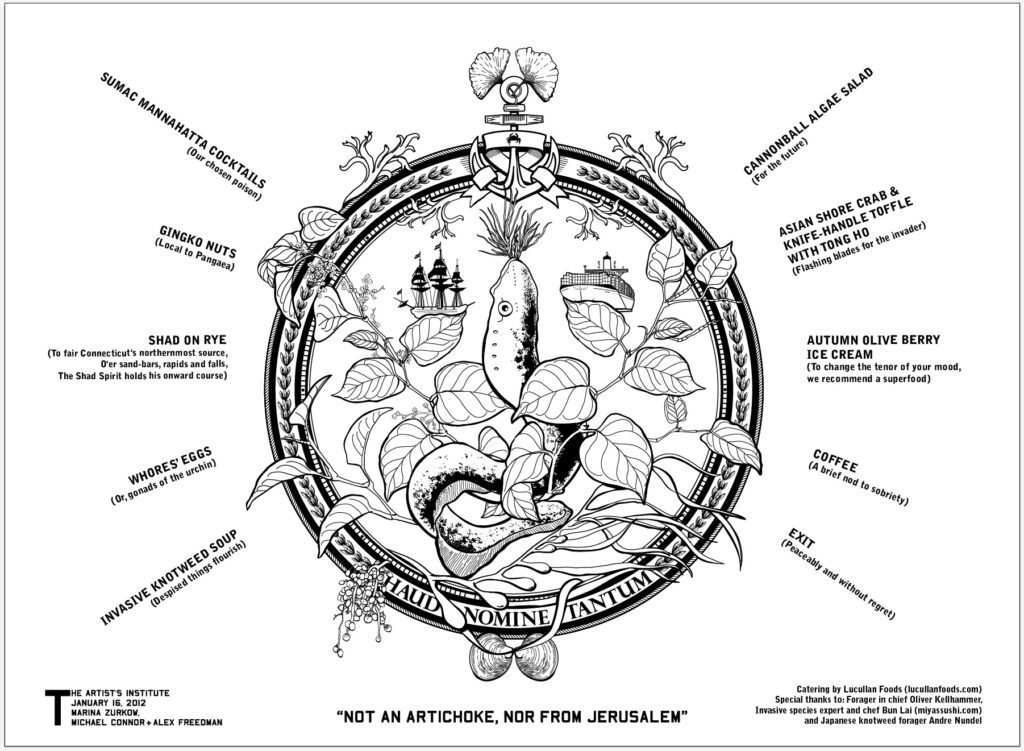

The Menu

The menu was presented as a limited edition print. Each course was accompanied by a toast prepared by either Michael, Alex or Marina:

Toasts

Sumac Manahatta

Sumac, sumach, summäq. What do you do when face to face with this cloned flowering plant in the wild? Ideally you’d want to bring your black light and see if it glows. But if you’re strapped for luminescence out in Brooklyn’s Marine Park in December, you’ll do what we did: triple check the Wild Man Steve Brill app and hope it’s poison ivy’s non-toxic next of kin. Alternatively you could avoid the foraging and just buy its derivatives: hummus, re-Phillip Morris American tobacco. First recorded in cuneiform by the Akkadians, this continental philanderer is a survivor. After all, how many tangy purple spices do you know that could survive in a shipwrecked medicine chest for 900 years?

To Sumac: the rhizome shooting mixer. (Alex)

Gingko

Remember the movie Jurassic Park? Well right now you’re about nosh on some bronto- food. Clocking in at a mere 270 million years old, the Gingko nut is a living fossil, not a nut. Less chemically complex than most bacteria, it is a proverbial loner without any modern relations. But unlike most, it’s got the chops to survive both natural mass extinction and Hiroshima size atomic bombs. Mis-transcribed as Gingko by Engelbert Kaempfer, a 17th century German globetrotter, the tree was anglicized in the 1770s as Maidenhair. Catching the eye of one Frank Lloyd Wright, male Maidenhairs have spread across America, with the female nut producing trees kept at bay to ensure public safety.

To ginkgo nuts, our fossilized friends, presuming you don’t eat more than 2-5 in one sitting. (Alex)

Shad

This is the Atlantic shad, latin name Sapidissima, or ‘very

delicious.’ It spent its life traveling thousands of miles up and down the East Coast, its mouth open to gather plankton and other treats. When the waters warmed in springtime, it swam up rivers like the Delaware, the Connecticut and the Potomac to spawn.

The arrival of the shad by the millions once marked the arrival of spring and the end of scarcity, concentrating an enormous mass of protein in inland waterways surrounded by half-starved humans. In 1686, William Penn claimed that a man could walk across the Delaware River on the backs of the shad. Its superabundance allowed the Lenape to congregate in greater numbers than usual, making its appearance an important annual social event.

Tonight, we eat cold smoked shad in the depths of winter on a cracker with crème fraiche, keeping in mind the very delicious springtimes of the past, and those of the future.”

(Michael)

Whore’s Eggs

“The etymology of the Sea Urchin complicates the phrase, Haud Nomine Tantum – the Latin motto that means “Not in Name Alone.”

The word urchin comes from the Latin ericius, a hedgehog, and also referred to a military engine full of sharp spikes.

But the resemblance between hedgehogs and urchins stops at its bristly exterior, and I’m sure a hedgehog tastes nothing like the sea urchin, whose anatomy is mostly taken up by its five bright, briny orange gonads. The gonad is the part we eat, evoking the oceany breadth of caviar, and the trembling texture of panna cotta.

There was another name for Sea Urchin, up and down the US eastern seaboard from the 19th century: Whore’s Eggs. It’d be nice to think this provocative name referred to the animal’s innards, mistakenly thought of as roe. But, it turns out, this was an innocent case of a local patois: in Newfoundland, when you leave the paddles of a boat in the water, the sea urchins lay eggs on them, thus, “oars eggs.” In Newfoundland those with early English roots often add the letter ‘h’ before words beginning with a vowel –happle, helephant, hair. Over time the descriptor became “whores’ eggs.” Some would even say whores heggs”

A toast to our next tasting, the Sea Herchin. She is served seated next to her umami kin, the Hoyster.”

(Marina)

Cannonball Jellyfish

“Who wants my jellyfish?

A poem by Ogden Nash

I’m not sellyfish!.

As we won’t be able to selly much fish in the future, it’s time to get down with our primordial friends as they take over our acid, warming, oceans.

The joy of jellyfish lies in their crunch. Malaysians call jellyfish ‘music to the teeth.’

A toast, to the Rise of Slime, and especially to jellyfish, the true beneficiaries of our great mess.”

(Marina)

Japanese Knotweed

“Japanese knotweed has been called “the asbestos of the gardening world.”

It was brought from Japan by Phillipp Franz von Sieblold, a surgeon stationed at the Dutch East India trading post at Nagasaki in 1825. The plant won most interesting new ornamental plant of the year’ in Utrecht, whereupon von Sieblold began his own aggressive marketing campaign to aid the plant in its journey to world domination. Because of its remarkable ability to sprout from pieces as small as a pinky nail cutting, the plant is now in the top 100 invasive species worldwide; it is found in 39 states in the US, and it is a federal crime to grow transport or remove in the United Kingdom. All of the Japanese knotweed found in both the US and the UK have been genetically traced back to the one female plant brought from Nagasaki to Holland.

Japanese knotweed is the perfect poster plant for the Anthropocene era.:

Climate change will continue to enhance her success, as she loves a good flood and a good drought, can replicate from a speck of stem and navigates fluently through eroded soil and even brick walls. But this voracious self replicating monster who spans the continents also bears gifts in the forms of nutritious food (good in a famine), and very good medicine. Since you can’t get rid of her, I’d suggest you invite her to the table, and ask for her assistance.

A bewitching cousin to rhubarb, this lemony soup will tonify your blood and heal a variety of ills.

A toast to one bad assed plant goddess, the great Japanese knotweed.”

(Marina)

Asian Shore Crab

“At 6 AM Saturday morning, chef Bun Lai went out foraging in Long Island Sound in the freezing cold. His quarry? The Asian shore crab, along with other native and invasive foods for our dinner tonight. The crab, native to the west coast of Asia from southern Russia to Hong Kong, has been appearing in ever-greater numbers along the East Coast, where it competes with native species like the hermit crab and feasts on foods like the blue mussel.

Bun is a big proponent of introducing invasive foods into our diet, and his restaurant in New Haven, Miyas Sushi, even has an invasive foods tasting platter. He brought us a jar full of Asian shore crabs, which have been living in a jar in the back for two days, as well as seaweed and wild oysters, which found their way into the dish we’re serving here tonight. The Asian shore crab placed on top of the dish can be eaten whole. But before we pop them into our mouths – here’s to

Bun Lai.”

(Michael)

Autumn Olive Berry

“And this evening we end with an ice cream of pines foraged by Bun Lai and a former USDA weed of the week award winner, the Autumn Olive Berry. Brought to America as a 19th century oriental ornament, this regenerative shrub has earned a prejudiced rap. Once deemed a savior for eroded land, it spread its red roots across America, siphoning off natives’ nitrogen, and earning the disdain of American horticulturists. It became the target of derisive memes, and stamped as an invasive species by the decedents of American immigrants. That was, until, scientists discovered that the berry is packed with lycopene, and may be one of the greatest agents in the fight against wrinkles.

So, I ask you all to join me in devouring this berry of youth in homemade ice cream. Cheers.”

(Alex)