MAM Contemporaries’ presented “The Cute, the Bad, and the Ugly.” Inspired by the exhibition Marina Zurkow: Friends, Enemies, and Others, on view at MAM (Sept 2011 – Mar 2012), this unique participatory food performance comprised a lecture led by the artist and a tasting catered by Gene Rurka, the celebrity exotic chef, hunter, and farmer, known for his appearances on television’s Animal Planet and as the force behind the Explorers Club’s legendary meals. As participants sampled delectable hors d’oeuvres and cocktails, they considered the intimacies of eating and learning, examining how we think about animals as food, both real and symbolic.

Event Documentation

Excerpts from the talk and tasting

In his 2001 book Botany of Desire, Michael Pollan asked: What Do Plants Want?

Marina Zurkow

Am I as a human the only one wanting something? Don’t other creatures equally feel like they are in charge? How do plants get us to do things for them? Plants get bumblebees to do heavy lifting, moving pollen around, while the bee knows she’s out there getting what she wants. Same with bears and seeds, cowbirds and water buffalo, mosquitos and malaria, human and dog. Darwin called this coadapation. But we – maybe all species — tend to deny credit to our partners and companions – be they food, friends or foes – editing them out of the equation.

This leading question: What Do Species Want? put a firm lens on my view of the world – that we all – all of us species — have agency and desires, just not necessarily the same desires nor the same modes of agency

This evening I will regale you with a select and condensed history of each of the three species, and you will taste each one as we go. Each compendium of dignified if not seriously respectable legacies and cocktail party facts should get you in the mood to taste each species perhaps anew, with a mind full of possibilities. We all know that eating affects health, mood, energy level, and focus. But what’s in it for the eaten? Are you ridding the environment of it, or begging for more? Can knowledge move a species from meat to animal, from eating your greens to eating this plant? Does a species want to be eaten? Are you dominating, or collaborating?

Japanese knotweed has been called “the asbestos of the gardening world.”

It is native to eastern China, Japan, and parts of Korea and Taiwan, though the variety of Japanese knotweed that has been introduced to the west is native only to Japan where it grows well in sunny volcanic soils. Along these freshly eroded slopes, knotweed’s far-reaching rhizomatic root system serves it well to establish a foothold, 9 feet down and 30 feet wide.

Any fragment of the root system or fresh pieces of stem can re-sprout. It can be transported to new sites by water, wind, as a contaminant in fill-dirt, or on the soles of shoes.

It tolerates a variety of adverse conditions including full shade, high temperatures, high salinity, and drought. It is found near water sources, in low-lying areas, waste places, utility rights-of-way, and around old home sites, and poses a significant threat along streams and rivers, where it disperses during flood events, rapidly colonizing shorelines and adjacent forest land.

It grows up to 2 inches a day. It will also grow right through cement.

In the UK, it’s classified as hazardous waste.

It is a perfect plant for the anthropocene.

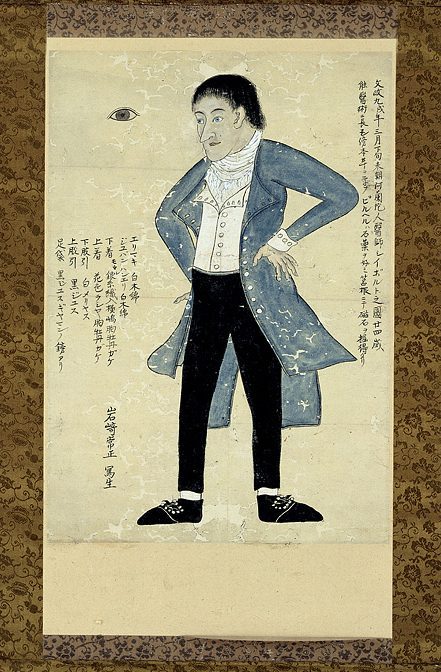

In the 1820s, Bavarian physician and naturalist Philipp Franz von Siebold was in the service of the Dutch East India Company at their trading outpost in Nagasaki Japan. A scandal over his illegal possession of some detailed maps of the country led to his expulsion, but by that time von Siebold had sent over 1000 living plant specimens back to Europe. One of these was Japanese Knotweed, which he named Polygonum cuspidatum.

From a commercial nursery that he set up in Leiden, Holland, von Siebold distributed plants throughout Europe. Japanese knotweed was awarded the Gold Medal from the Society of Agriculture and Horticulture at Utrecht in 1847 for the ‘most interesting new ornamental plant of the year’, and von Siebold began an aggressive marketing campaign. Using its vigorous growth habit, its penchant to form dense screens and stabilize erosion as major selling points, Japanese knotweed was sold as an ornamental fodder plant loved by both bees and cattle, with medicinal value for people as well. Sales were widespread.

In 1850, van Siebold sent an unsolicited package of plants, including Japanese knotweed, to the Royal Botanical Gardens in London. Thereafter it was sold and distributed by a large number of commercial nurseries and amateur enthusiasts.

At first, 19th c English horticulturists swept up in the rage for “wild” gardens, gave glowing testimonials:

“large and noble tufts of lively green, which increase in beauty from year to year”

Victorian “Wild Garden” advocate William Robinson

“..is the handsomest, easiest grown, hardiest, most useful plant for London gardens”

Mrs C.W Earle 1897

By the end of the Nineteenth Century, the dangers of the plant were becoming apparent. An account published in 1887 observed how knotweed kept appearing “unexpectedly in nearly every piece of cultivated ground.”

This plant had no intentions of leaving, ever.

“We should not forget the quick ways of the great Japan Knotweeds growing fast and tall”

Garden designer Gertrude Jekyll, 1900

“…easier to plant than to get rid of in the garden”

THE ENGLISH FLOWER GARDEN BY JOHN MURRAY 1907

Once an invited guest, she had outlived her welcome. Gardeners acting in the time honored manner, dug up pieces of the roots, and threw them away, thus promoting her proliferation. Despite the warning signs, it wasn’t until 1981 that the British government created laws that explicitly controlled knotweed’s sale and spread. It is only a menace outside of its natural environment, where it is kept in check by natural means – in Japan at least 30 species of insect and 6 species of fungus feed on the plant. Outside of its natural habitat, these species do not exist and, with no natural predators, the plant is thriving. In 2010, knotweed was recorded in 70% of the 10 x 10km recording squares in Britain.

Herbarium records show that the knotweed was being grown in the US by 1877. In the US now, the plant is found in all but 6 states.

“In a number of senses Japanese Knotweed is an extraordinary plant. Its vigorous powers of vegetative reproduction mean that it has been able to spread to all parts of the British Isles without the aid of sexual reproduction. “

These are the words of Dr. John Bailey – Knotweed’s Principal Experimental Officer, Biology Department University of Leicester, England.

He continues:

“I never tire of telling people, I am much more interested in the sex life of Japanese Knotweed, than I am in killing it! A lifetime’s study of Japanese Knotweed has revealed a fascinating story, a giant female clone with tendrils stretching from Japan to Europe then onwards to North America.

A riches to rags story – a plant once an expensive and cosseted prize-winner, a plaything of the wealthy, reduced in the space of couple of decades to a life in the gutter, the road and canal side. A plant that has spawned a mini-industry dedicated to its eradication and so loathed in Britain that it is… a criminal offense to move as much as one atom of Japanese knotweed from one site to another.“

Since Bailey wrote this, he informed me that recent molecular genetics studies of the plant indicate that all of it – all of it – can be traced back to the specimen Siebold brought in the early 1800s from Nagasaki.

But now for the good news!

I read from by Robert McCanless’ article in the Long Island Garden News,

“Once a glam garden ingénue, Japanese knotweed fell from such heights into the demon registry of World’s Most Invasive Species. Like its hustler, von Siebold, the plant has a good side. It is loaded with the antioxidant Resveratrol, the substance also found in the skin of red wine grapes. Most of these supplements on the market are derived from Knotweed. Also on the plus side – among us who have watched beloved vegetables die horribly from Late Blight and Powdery Mildew – is a new fungicide based on an extract of Knotweed, called Regalia.”

What McCanless doesn’t mention is that the plant’s medicinal properties have long been recognized.

Here is a short excerpt from Shikigami, a Japanese foraging and sustainability blog:

“When I look online for knotweed, I get pages and pages of how to eradicate it. Why are we such haters? We need to be lovers people! Japanese knotweed is one of those plants that elicitc an awful lot of ill feeling but it is truly amazing and deserving of much respect. The common English name “knotweed” displays such ignorance that from here on I shall use the Japanese name: itadori.”

A literal translation of ita-dori would be pain puller or, removes pain.

This is a name that clearly tells us something about the uses of the plant and the high regard in which it is held. Plant people of Japan, Korea and China have traditionally used the roots of itadori as an anti-inflammatory, as a laxative, for oral hygiene and cardiovascular health, for treatment of acute hepatitis, kidney stones, high cholesterol, and skin rashes amongst a host of other uses.

In Chinese Medicine, Japanese knotweed is called Hu Zhang. The Compiled Essence of All Medical Works says:

“the herb is sweet, bitter, and acrid in flavor and warm in nature; it tonifies the muscles and bones and increases strength.” In Prescriptions Worth a Thousand Gold, it is said that “mixing the decoction of the herb with aged wine is effective for treating abdominal mass, tinnitus, heaviness of the limbs, irregular menstruation, and impotence.” In Chinese medicine today, hu-zhang is said to clear up heat, invigorate blood, detoxify, and disperse swelling.”

Western scientists are researching the plant’s uses in Lyme disease and prostate cancer.

And last but not least, Japanese Knotweed is edible and tasty when harvested early in spring. The plant is high in Vitamins A and C and can be prepared like rhubarb, sorrel, or asparagus. It’s in the buckwheat family along with rhubarb and shares rhubarb’s sour flavor.

Its masses of small white flowers bloom late in the season, providing a big boon to bees.

Most people who are familiar with Japanese knotweed in the West have no idea about its beneficial properties or its long history in the East. The only people who really engage with the plant here are DIY foragers in very local pursuits.

We can consider Japanese knotweed as the poster child – or poster plant – for the anthropocene era. Climate change will continue to enhance the success of this super-plant, who is hardy and loves a good flood and a good drought, can replicate from a speck of stem and navigates fluently through eroded soil and construction debris. But this voracious goddess who spans three continents also bears gifts in the forms of food (good in a famine), drink, and medicine. Since you can’t get rid of her, I’d suggest you invite her to tea to negotiate.

This evening’s preparation of Japanese knotweed is a post colonial mash up, to honor the first Western encounter with the plant by von Siebold. We are tasting Japanese knotweed chutney made with coconut, currants, dates, and asian chile, over a traditional Dutch Gouda cheese and served on rye bread– the latter two being common Dutch foods at the time the Dutch East India Company had their trading post in Nagasaki, Japan. It is served on a bed of invasive dandelion leaves.

Platters of Japanese knotweed are now passed throughout the audience

Platters of Japanese knotweed are now passed throughout the audience

Donna Haraway in her book “When Species Meet” writes that

“Companion species “break bread” together at table; it’s in the word itself—cum panis, with bread. Who is on the menu at this table is a question of ethical, political, and ecological urgency.”

Bear with me a little longer as I conflate who is on the menu with who is at the table!

For I want to go back to the idea of needing to love what we eat, and whom we break bread with. We have seen this evening with Japanese knotweed that a species this hated is not thought of as food and is most unwelcome at our table. But invasive species have asserted their staying power, and they want to be eaten and loved!

We would do well to think and behave in a livelier way about these species as our kin.

We may think only we are at the table – we and our chosen others – but who has really come to dinner, whether we like it or not, includes other species who participate in our global peregrinations, either by volition, accident, or our own fancy. I hope tonight’s talk and tasting begins to animate the beautiful, disruptive network of participants; to dismantle the idea of our human supremacy; to challenge our biases and short-term memory; and to consider that there exists kin beyond our own kind.

Our hierarchical assumptions about our human dominion at the global table, and even our claim to being a coherent, bounded entity called Homo sapien or “me,”– are daily being taken apart by science, and reconsidered by philosophy.

Each of the species we looked at, heard about, and tasted tonight — European rabbit, Japanese knotweed, and the truly international Wild boar – have complex and often conflicting roles in a variety of contexts. Perhaps next time you eat spinach, or a Littleneck clam, or a Big Mac, you can taste with all your senses the network of stories, histories, and of course the real plant or animal at the other end of the transaction we call eating.

If we are all kin, then we might as well get to know these pushy relations.

Thanks to Gene Rurka for his chef skills, time and generosity, to forager and wild food expert Holly Drake, and to the Montclair Museum, to curator Alexandra Schwartz and development coordinator Emily Washington and to everyone who helped this evening, thank you.