Research Journal

-

June 28, 2009

Allenheads – Land inside out

Tags:Things of course are nothing like what they appear. Land like any other time-based and event-based instance needs to be decoded or requires literacy to understand its stories.

Last week I was generously welcomed to Allenheads Contemporary Arts by founders & artist producers Alan Smith and Helen Ratcliffe, and by Hannah Marsden, curator of their recent show Exploring Nostalgia (see earlier post on dead moles in dresses). Alan gave me an intense tour of the land, 2 hours of condensed experiential learning by car and foot – jumping up and down on the watershed land (a spongy trampoline), looking at charming, flower-strewn brooks (actually garbage middens from 19th c lead miners), and learning to read the vertical scars on the hills – channels made by huntsmen to drain the highland moors for better pheasant and grouse hunting conditions. Underground, a white-lime painted maze of tunnels that takes you forward in time as you go further in (newest last); this work of burrowing has, like worms, left giant-sized man-castings on the surface which look like naturally picturesque bumps and hillocks.

Sheep up on the high moors, Allenheads

Allenheads, old house/smelter remains

Stream at bend of the original cart road into Allenheads

Alan Smith

Allenheads Contemporary Art family members Kaiser and Messerschmidt

Allenheads community member I thought there was an odd and distant kinship to New York/Staten Island’s Fresh Kills Landfill, of a long term land shape that’s formed from the inside out, entirely by man (see “Why Call Them Landfills? They are dumps, eyesores, middens and disgraces.”)

Fresh Kills – Then and Now (over the years) -

June 28, 2009

Invasion of the Pirri-pirri

Pirri-pirri bur (Acaena novae-zelandiae) is an invasive species concentrated in the dunes at Holy Island (an din parts of northern Ireland). Wily and sculptural little stick-ems that break into seedy pieces when you try and remove them. Would be fun to design a suit to take a walk in, ending up covered in these atomic wonders. But don’t turn your dog into a pirri-pirri-collecting artwork – it’s apparently very painful for the canines.

Pirri pirri is not a native to Britain and is thought to be originally from New Zealand, possibly brought over in shipped consignments of wool. During and just after the seeding time the tiny burrs are exceptionally sticky and very difficult to remove.

Apart from the damage to the dog there is also a real danger that the seeds come over to the mainland and set themselves in dunes or gardens. (Berwick Advisor)

-

June 27, 2009

Holy Island Tourist Owl

I usually don’t post personal thrills (liar) but I have a soft spot for owls. I’d only ever gotten to pet a taxidermied one. This is a 4 year-old barn owl rescue; some teenagers brought their imprinted charges out to Holy Island from Berwick on Tweed, to raise money for their parents’ rescue operation. There was this one:

… and this one – a 9 week old abandoned tawny owl:

…and a peregrine falcon and an american kestrel. and 2 very keen and knowledgable teenage girls.

-

June 27, 2009

Druridge Bay

Invasive glove. But nice looking (and dominant). Note coal dust in sand.

- Invasive Brick.

- Native lugworm castings

-

June 27, 2009

Drawing IV (sketch for a taxidermy arrangement)

-

June 25, 2009

Drawings III (reds)

-

June 24, 2009

Eating Thy Enemy (animals)

1. Slipper Limpet (Crepidula fornicata)

Invaded: Accidentally introduced in 1887 along with American Oysters.

Image Steve Trewhella – Chain of Crepidula fornicata. The slipper limpet has invaded the European coast all the way to Spain, especially along the coasts of Brittany and Normandy. It feeds by filtering water and consuming a large quantity of plankton, thus chasing away mussels and oysters, which are also filtering mollusks, from their original environment.

Easy to find, the slipper limpet attaches itself at a shallow level, not more than 10 m deep. At low tide, they can be easily collected… Its meat is more tender than the limpet; it is delicate and requires only minimal cooking; it has a slightly nutty taste that should be brought out; its flavor is subtle and should not be masked; (from Worldwide Gourmet)

***

2. American Bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana)

Invaded: increased in the late 1970’s, with the sale of tadpoles in small quantities as pets. Although there have been numerous escapees across the country a breeding population was not recorded until 1999.

American bullfrog Introduced as a pet in the 1970’s this voracious predator is a danger to much UK wildlife. (Introduced Species UK).

Large specimens have been known to catch and swallow small birds and young snakes; its usual diet includes insects, crayfish, other frogs, and minnows. Attempts to commercially harvest frogs’ legs have prompted many introductions of the American Bullfrog outside its natural range. (enature.com)

They can be barbecued, or fried, or sauteed. If you are going to harvest them yourself, then follow these guidelines:

Frogs are a breeze to clean. Rinse the frog, then grasp it behind the front legs with its head in your palm and place it belly down on a cutting board. Stretch the hind legs out and cut with a cleaver or heavy knife above the hip. Try to keep the legs attached as a pair to ease skinning and cooking. Work your finger under the skin between the frog’s legs. Then, pull the skin down the legs to the ankles, like peeling off a pair of tube socks. Cut off the feet and skin with a sharp knife and toss this tasty treat to the friendly barn cat keeping you company. Place the legs in a freezer bag with a tablespoon of salt per gallon bag of frog legs, fill the bag with water and refrigerate or freeze. This will avoid freezer burning the legs. The hip bones can be sharp, so double bag. (from The Missouri Conservationist)

So, does frog really taste “just like chicken”? Well, only if one of your chicken’s grandmothers was messing around with a fish – it has just a faint suggestion of fish flavor.. The flesh is mild and less stringy than chicken, more like Alligator actually. Frog cooks quite quickly, 20 to 30 minutes at a simmer depending on size. When it is done the legs will separate into separate joints and the meat will start to fall off the bones. (from Clove Garden)

***

3. European Rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus)

Invaded: first introduced by the Romans, and then re-introduced by the Normans in the 12th century to provide meat and fur. (even better if you get it as roadkill)***

4. Ruddy Duck (Oxyura jamaicensis)

Invaded: Escaped from captivity in the 1940’s

The Ruddy Duck (male) “over-sexed and over here” (BBC News)

***

Misc Animals – Chinese Mitten Crabs, Grey Squirrel, American Signal Crayfish, Zebra Mussels, and many more non-human animals are covered in the Guardian article mentioned here.

-

June 24, 2009

Eating Thy Enemy (plants)

I’m looking at the relationship between invasive species and their causes.

Taking a rather primitive approach, I want to offer up this solution: Eat Thy Enemy.

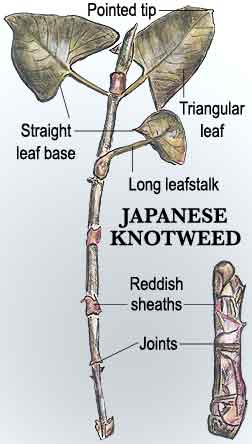

Many promise to be delicious–1. Japanese Knotweed (Polygonum cuspidatum, Fallopia japonica)

Invaded: 1850’s. Imported from Japan as ornamental“tastes like rhubarb, only better” – Steve Brill

Fantastic information on knotweed on Wildman Steve Brill‘s site.

Euell Gibbons’ “Stalking the Wild Asparagus” wrote that Japanese knotweed tasted like rhubarb and was good eats — apparently you could make pie, jam and even a tasty soup with it.

Back home, I peeled the bottoms of the foot-long stalks, removed its leaves, and sampled my polygonum notch-by-notch. Japanese knotweed is crisp and surprisingly tart raw, rather like an immature Granny Smith crossed with a tomatillo. Parboiled, the tips have asparagus-like first notes, followed quickly by a tart, high-in-Vitamin-C-punch — there’s a reason why it’s often compared to rhubarb.Some recommend steaming it as a side dish or adding it raw to salads. I added it to tomatoes, cilantro, shallots, habanero pepper, and lime for a twist on salsa fresca. (from The Stoop, Ava Chin’s New York Times’ blog

Plants for a Future rates this plant rather well – although warns about photosensitivity from knoteweed’s oxalic acid content (same as rhubarb or sorrel).

***

2. Pennywort (Hydrocotyle ranunculoides, Centella asiatica)* a.k.a. gotu kola

Invaded: 1980’s. Introduced commercially for use in garden ponds and aquaria

Stem, leaves and roots are edible. Used in salads, drinks, rice dishes, raita in Asia. Has health benefits attributed to it. (from Practically Edible)

Big glowing dissertation on its gustatory and salutory properties: Pennywort: The Elixir of Life

***

3.Hottentot Fig (Carpobrotus edulis)

Invaded: 1886. Introduced from South Africa to stabilize soil and dunesThe creeping, smothering mats of Hottentot Fig out-compete native plants and reduce biodiversity by competing for nutrients, water, space and light. It is a plant of coastal habitats and as such threatens some of the most sensitive ecology in the UK.

On the upside, it has edible fruits, although sour can be made into jams. Not invasive (yet) in the north; mostly restricted to Devon/Cornwall area (NNSS)

Fruit – raw, cooked, dried for later use or made into pickles, chutney etc. There is very little flesh in the fruit and it must be fully ripe otherwise it is very astringent. Mucilaginous and sweetly acid. Leaves – raw or cooked. Succulent, they are eaten in salads and can also be used as a substitute for pickled cucumber. We find them too mucilaginous to be enjoyable. (Plants for a Future)

***

4. Common Water Hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes)

origin: South America. Invasion date unknownThe plant is used as a carotene-rich table vegetable in Taiwan. Javanese sometimes cook and eat the green parts and inflorescence. (Duke, Handbook of Energy Crops) (also mentions that “eating the plant may induce itching,” but perhaps only if raw?)

***

5. Himalayan Balsam (Impatiens glandulifera) a.k.a. Jewelweed

Invasion: 1839. Western Himalayas.Himalayan Balsam has been eaten in India for hundreds of years…the seeds are eaten, having a nutty flavour, while the young leaves are used as a vegetable.(from Eat Weeds UK)

Young leaves and shoots – cooked… Seed – raw. A delicious nutty flavour, but difficult to harvest in quantity mainly because of their exploding seed capsules which scatter the ripe seed at the slightest touch. An edible oil is obtained from the seed.The plant is used in Bach flower remedies – the keywords for prescribing it are ‘Impatience’, ‘Irritability’ and ‘Extreme mental tension’. It is also one of the five ingredients in the ‘Rescue remedy.’ (Plants for a Future)

***

6. Wakame (Undaria pinnatifida)

(currently not a threat in Northumberland)This is delicious in soups, tsunomono (vinegared seafood), etc. Commonly used in Japanese cooking. High in antioxidants and vitamins.

***

7. Dead Man’s Fingers or Green Sea Fingers (Codium fragile subsp. tomentosoides)

Invaded: stats from plantlife.org.uk

I suspect it is edible, but need confirmation.

***

8. Pirri-pirri bur (Acaenia anserinifolia) a.k.a. bidgee-widgee

Invaded: Native to New Zealand. Suspected import in “contaminated” wool.

Sticks to you like sculptural velcro and breaks apart easily. Has made significant inroads on Holy Island and in norther Ireland.It’s in the Rosaceae family; and according to Plants for a Future, the leaves can be used for tea and are Antiphlogistic; Diuretic; and Vulnerary. (Plants for the Future)

Pirri-pirri bur ***

9. Wireweed (Sargassum muticum) a.k.a. japweed

Invaded: TBDAnother lovely addition to salads, having little exploding flavours when eaten. Cooked with fish, scallops, made for each other. (foods wild)

***

10. Water Chestnut (Trapa natans)

Invaded: TBD

note: Must be cooked before eating, the seed/fruit contain a toxin that is destroyed by cooking.

the edible seed (don't forget to cook it) ..floating annual aquatic plant, growing in slow-moving water up to 5 meters deep, native to warm temperate parts of Eurasia and Africa. They bear ornately shaped fruits that resemble the head of a bull, each containing a single very large starchy seed. It has been cultivated in China for at least 3,000 years for these seeds, which are boiled and sold as an occasional streetside snack in the south of that country.(wikipedia)

Singhara Flour / Water Chestnut Powder:

StarchWater Chestnut Flour is made from dried, ground water chestnuts. The nuts are boiled, peeled, dried then ground into flour.

The flour, which is actually a starch rather than a flour, is bright white fine powder.

It’s primary use is as a thickener. It is also used in Asian recipes to make batters for deep-frying.Water Chestnut Flour gives a light crust when used for dredging, and stays white as a coating even when fried.

It is very different from “real” chestnut flour, which is sweet.

Cooking Tips: Mix with water first before adding to hot liquid as a thickener. (practically edible)Singhara is Indian water-chestnut, triangular in shape, with thick red…ish green skin, with 2 small spikes at the top. It has milky white, lightly sweet flesh. It is eaten like a fruit when fresh, made into bhajies and curries when halfway mature and made into flour when completely mature and dry.

Recipe for Singhara Flour HalvaYou can also make Singhara poori.

***

-

June 24, 2009

Nutkin’s Last stand, a film

Tags:A US filmmaker, Nicholas Berger, made an 18 min doc in 2008 looking at the red vs grey issue, and came out for the reds. I have yet to see the film, but I’m happy someone made it and blurred any nationalist allegiances.

-

June 24, 2009

Invasive Plants defined

Tags:Definition from Plantlife International:

At the end of the last ice age, and up until around 8,000 years ago, Britain was connected to the rest of Europe by land. Plants and animals moved north as the ice retreated, taking advantage of new habitats available to them. When the land bridge was flooded most plant species would no longer arrive in Britain of their own accord, but would rely on being brought here by people. This ‘closure’ of the land bridge is the widely-accepted cut off point for determining which plants are native and which are considered to be non-native.

‘Non-natives’: Plants that were brought to Britain by people, either intentionally, including crops and ornamental garden plants, or unintentionally, for example by being inadvertently mixed with crop seeds.

Within this ‘non-native’ category it is common to distinguish between plants brought to Britain before 1500 AD (called archaeophytes – literally ‘ancient plants’) or after 1500 AD (neophytes – literally ‘new plants’).

This distinction roughly correlates (in Europe at least) with the rise of long-distance cross-oceanic trade. In other words, when species started to be moved frequently across biogeographical barriers. So the plants and animals brought to Britain by the Romans and the Normans are archaeophytes, whereas those brought here from the Americas or the Far East are neophytes.

Archaeophytes include many arable plants that have declined substantially in Britain in recent years. Neophytes include many widely-cultivated garden plants. People who are concerned about non-native invasive species are usually most worried about neophytes. One reason for this is the breaching of those biogeographical barriers, and so the increased likelihood that native species will have no coping strategies to deal with the newcomers.

Another reason people are particularly wary of neophytes is the lag effect commonly displayed by non-native invasive plants. Non-native invasive plants are often present in Britain for several years before ‘taking off’ and beginning to cause problems. Neophytes are more likely to still be in a lag phase than archaeophytes.

‘Non-native invasives’: Some plants grow rapidly, can produce many thousands of seeds, or can reproduce without seeds. They can colonize a habitat and quickly ‘take over’, displacing native plants by smothering them, out-competing them for resources, or even poisoning the soil around them so that other types of plants can no longer grow there.

Most non-native plants are not invasive and pose no threat to the countryside. Plantlife has no desire to stop people selling, buying, using or growing these plants. What we are concerned about is the small number of ‘non-native invasive’ plants that cost both the environment and the economy dear.

So why do some plants become invasive?

Three key groups of factors commonly combine to enable a plant to become invasive:

1) In their natural ranges, invasive plants are often common but not problematic. Their extent is limited by pressures placed on them – for example from herbivores and fungal diseases. When plants are placed in a new environment, these containing pressures are rarely transported too, giving the new plants an advantage over native plants which are still affected by pathogens and herbivores.

2) Invasive plants often have characteristics such as fast growth, prolific seed production and/or an ability to spread vegetatively (without the need for seeds), an ability to tolerate wide ranges of growing conditions (soil types or water pH, for example), and a range of ways in which seeds can be spread locally and over larger distances (say, by wind, water or animals). People are often instrumental in spreading invasive plants.

3) The environment that the new plant is placed in is in some way disturbed or damaged, providing the opportunity to invade. For example, in polluted water systems, more nutrients are available than can be used by the native plants present, giving the invading plants an opportunity to get established.