Research Journal

-

June 12, 2009

Kittiwakes in the nature/culture wars

This from the BBC/Tyne online

“The Kittiwake, a small seagull, could be driven off its nesting sites on the Tyne Bridge by Newcastle City Council.

The birds are at sea feeding on fish offal discarded by trawlers and when they return in the spring to nest they may find that the City Council has netted off their nesting sites on the Tyne bridge.They used to nest in the Baltic Flour Mills but have been driven off by the cultural aspirations of Gateshead. Gateshead Council provided a nesting tower but this has been moved down river.

The renovation of the Baltic Flour Mill on the Gateshead side of the Tyne took away access to a Kittiwake breeding site on Tyneside.

Now, in response to complaints from local residents about the mess and noise from Kittiwakes, Newcastle City Council is considering netting the Tyne Bridge to prevent nesting.. IIt is clear that the Bridge has become an important breeding site for these birds. Whilst there are of course much larger breeding colonies in the UK, the Tyne Bridge is the furthest inland breeding site for Kittiwakes in the world.

Kittiwakes on the Tyne Bridge

The Tyne Bridge -

June 12, 2009

Cutifying cancer

The Newcastle Metro is plastered with appeals for oesophagal cancer using the ‘cute’ animal logo of the “oesophogoose:”

The Oesophagoose -

June 12, 2009

Grant Burgess, The DOVE Marine Laboratory

Tags:I had a tour, some lessons and an intense conversation with Grant Burgess, Director of the DOVE Marine Laboratory in Cullercoats, Northumberland (it’s part of Newcastle University’s Marine Biology Dept).

Dr. Grant Burgess This is one of the few labs that has a steady supply of seawater pumped through the building’s plumbing. It flows through the lab taps!

DOVE Marine Laboratory I learned a bit about Anton Dohrn, who built the first Marine Station in Naples in the 1870’s, and actually implemented an art-science interface, by hosting concerts, and art events within the lab… Grant came to my talk at ISIS, and is clearly very open to the interplay of hard science, and the evocations that art can muster, measures to teach and incite…

Grant’s lab foci include: “Novel bioactive compounds from marine bacteria, chemical defense in marine microbes, antifouling compounds from marine bacteria, microbiology at high pressure, sponge microbiology, biofilms, and more recently marine fermentation and bioprocessing.”

In lay terms, he explained that the lab’s working on turning algae/fungus into an OMEGA 6 source, since we no longer have fish as a viable source for the nutrients; and using algae as an energy fuels. The lab also researches the medicinal potential of sea slugs, and ways to zap ballast water of invasive species. Among other things. I got a crash course in quorum sensing– the ways bacteria make language out of molecular signaling, in order to act in concert when a quorum is reached.

The lab’s growing algae on the roof ( even in winter in the limited sunlight) in these cheerful, workaday aquaria:

Roof of DOVE We took a tour through the remains of the Victorian era public aquarium, where we met a very curious plaice, who came right up to the window, very self-possessed and clearly eager. Am I anthropomorphizing? Is it useful? Can one attribute motivation without human descriptors, and attribute thoughtful agency to non-human animals?

We also had some very speculative conversations on invasive species – the embedded racism and selective designations inherent in the condemnatory term, and how the line is in slippery flux between “introduced” and “invasive.”

I like these hybrid spaces – of thinking, working, making.

Front doors of DOVE -

June 11, 2009

The Ouseburn

Laura Harrington in the Environment Agency's Electric Car I went for a walk with Laura Harrington, who is artist-in-residence at Environment Agency. We walked by the Ouseburn – a small river off the Tyne in a surprisingly quiet and neglected-seeming part of Newcastle not so far from the center, after driving with her in the EA’s funny little electric car.

This next pic is by someone on flickr – Paul J White – who calls Ouseburn “the cradle of the Industrial Revolution.” I bet some brief research would show this brownfields holdover as a pretty interesting ecosystem now.

photo: Paul J. White -

June 11, 2009

Dead Moles in little dresses

- Artwork at Allenheads, “Exploring Nostalgia,” photo by Sharon Bailey

Crazy… Moles are traditionally nailed to fences – it’s a way of counting coupe so the molecatcher gets paid. More on this after I visit Allenheads Contemporary Arts (ACA), an arts centre in the moors of rural Northumberland.

Just for context, I looked into molecatchers and found this gent “Jeff Nicholls the GRASS SHARK HUNTER. ” Of course he’s in the Guild of British Molecatchers:

He’s written some eponymous books that have met with rave reviews — “Anyone who suffers from moles will find Jeff Nicholl’s Molecatcher a long awaited lifeline.”

But I haven’t found too many technical pics on his web site, except this one, tugs at the heart strings (especially after petting a very soft, dead mole at the taxidermy studio of Eric Morton):

But this is what I was looking for:

Dead moles on a barbed wire fence 3 km from Whitley Chapel, Northumberland, Great Britain. Copyright Les Hull I’m of two minds about this – it’s traditional warfare between cultivator and cultivator; and it saddens me, to see them hung by their nosies.

- Artwork at Allenheads, “Exploring Nostalgia,” photo by Sharon Bailey

-

June 11, 2009

The Natural History Society of Northumbria

Seeing Thomas Bewick preparatory drawings in the flesh at the archive today, with archivist June Holmes. Yes, I don’t get out enough and don those WHITE GLOVES.

June Holmes, Archivist It was a thrill. Bewick’s work is astonishing – firstly, because of the level of detail at such a tiny scale, but also because he worked varying degrees of the detail into the drawings, which he transferred onto the blocks, and then did an enormous amount of the detail work on the block itself (in negative — did he see the world in reversed lines as well?). June Holmes said the animals he knew well just didn;t require that much preparation… roosters, dogs, local common birds, foxes…

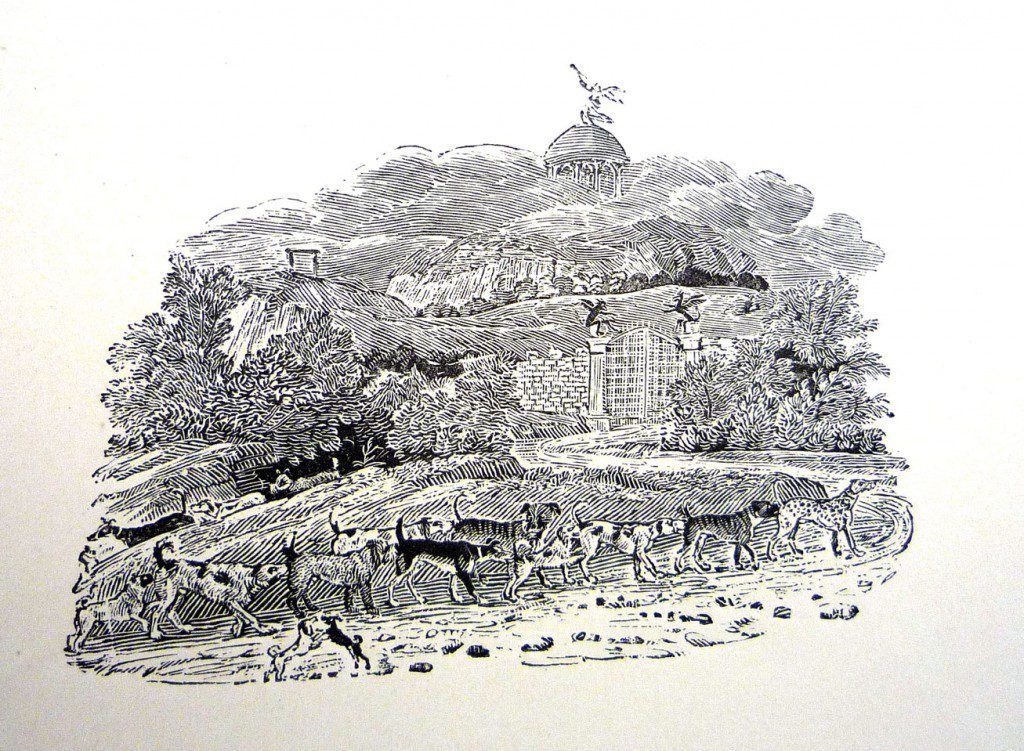

Here is an engraving that never got published.It is one of his allegorical/anecdotal “tail-pieces” – the original is about 3″ wide, max:

Dogs Sniffing Dogs (courtesy The Natural History Society of Northumbria) The Bewick Society has a lot of vignettes online – these were used as filler at the bottom of pages, but are far more than tailpieces- Bewick called them his tale-pieces, and they are worlds of their own, highly detailed miniatures that construct a natural history of everyday life, often with a memento mori quality. I’d always thought of his use of inscribed text upon the rocks as a way to illuminate the fact that the landscape itself is a kind of text, but apparently, he thought the landscape could become a site of morality, and he fancied to make it carry the word of God, so to speak (I think I’ll continue to believe in the “natural” texts of distinguished, dramatic landmarks, many of which have nicknames as wayfinding markers – synesthetic mnemonics in which being, place, and folkloric inscription tangle up to make geography).

Image from Thomas Bewick's Memoir

from Bewick's Book of British Birds -

June 10, 2009

I am Starry eyed for taxidermists

… made explicitly poetic by two visits I had in the last week with taxidermy artists.

First was Emily Mayer, an amazing animal artist in Norwich. She lives + works in an old workhouse infirmary, and makes exquisite sculptures – some taxidermy, some found materials like scrap metal and plastic bits and downed wood (see the recent exhibit at Campden Gallery here). She’s also taxidermist to the (art) stars.

Emily Mayer's beautiful clean exhibit space upstairs from the workshop

Emily Mayer, my godchild Susan O'Flynn, and Violet Second was my morning visit to the temporary workspace of Eric Morton, taxidermist for the Great North Museum (née Hancock Museum) here in Newcastle on Tyne. When I spoke to him on the phone he said he was in the process of moving his workspace and there wasn’t much around. Right. He’s genius. I asked him if he has animals festooning his home, and he said “no! that’s like bringing work home. I collect clocks.” I can only imagine.

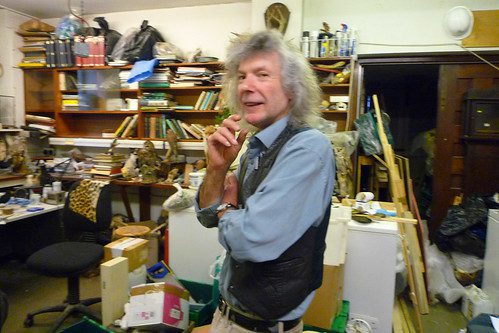

Eric Morton at his workspace at Newcastle University

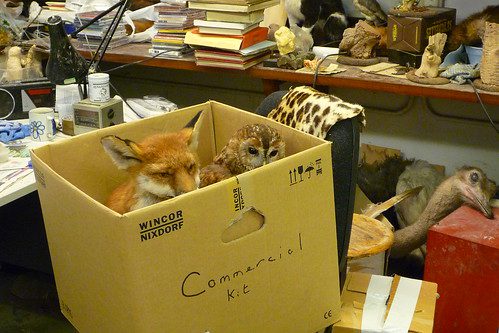

Exhibit A

Moving Day It is no mean thing to be able to pet animals– albeit dead ones — like owls, foxes, and moles.

More photos here chez my flickr zone.

-

June 8, 2009

Owen Humphreys chronicles the squirrel war

Owen, I like to imagine that you are Chief Squirrel Liaison for the Guardian. Owen, can you hear me? Do you heart the Red and hate the Grey, as much as your photos convey?

BOUNTY. photo by Owen Humphreys

Another beautiful Owen Humphreys image, from the Guardian -

May 22, 2009

cyanobacteria is burning

Tags:A nasty sea weed, Lyngbya majuscula is thriving from Tampa Bay to Sidney.

It’s not a weed – though it’s known as fireweed; it’s actually a “a benthic filamentous marine cyanobacterium” (National Research Centre for Environmental Toxicology) that grows on seagrass, and it does very well in low-oxygen environments, ripe for a bloom when there are not so many fish to stave its spread.

Its effects are toxic to humans- (itchy rashes, painful boils, and respiratory problems on exposure)

It is also known as Mermaids Hair.

When Lyngbya grows in sufficient mass it will detach from the substrate, seagrass beds and other areas where it typically grows and form floating ‘rafts’ which are then moved by prevailing winds and currents in the bay and eventually onto foreshores. (Redlands, Australia)

A raft of Lyngbya majuscula LA Times’ environmental reporting is very good, but very apocalyptic. I didn’t say “hyperbole.”

July 2006 LA Times “A Primeval Tide of Toxins”

-

May 18, 2009

Fairy Cattle

Wild Chillingham Cattle are known as “fairy cattle” for their small size and tufted red fur in their ears; they are genetically distinct from any other (including their relatives the White Park Cattle, who have black ear fur).

Fairy Cattle (uncredited/undated on the Chillingham Castle web site) portrayed as a bloody pre-Raphaelite floral