Research Journal

-

September 24, 2020

A Catholic legacy, naturalized

(more…)

A recent article “A New Theory of Western Civilization” (The Atlantic) leads me to wonder about connections between this giving context to the rise of western ideas of the individual self, and the “widely held” beliefs ingrained in Wise Use and Property Rights movements.

The Atlantic article is a deep look into evolutionary biologist Joseph Henrich’s “ambitious theory-of-everything book”, The WEIRDest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous. I think it offers dimension to the overlooked “how’d we get here, and then export it as if it’s always been this way” and helps me personally stop saying “humans” as if al of us descend from this now-dominant ideology that eagerly seeks to erase its historical coming-to-be.

Human beings are not “the genetically evolved hardware of a computational machine,” he writes. They are conduits of the spirit, habits, and psychological patterns of their civilization, “the ghosts of past institutions.”

One culture, however, is different from the others, and that’s modern WEIRD (“Western, educated, industrialized, rich, democratic”) culture. Dealing in the sweeping statistical generalizations that are the stock-in-trade of cultural evolutionary theorists—these are folks who say “people” but mean “populations”—Henrich draws the contrasts this way: Westerners are hyper-individualistic and hyper-mobile, whereas just about everyone else in the world was and still is enmeshed in family and more likely to stay put.

Starting around 1500 or so, the West became unusually dominant, because it advanced unusually quickly. What explains its extraordinary intellectual, technological, and political progress over the past five centuries? And how did its rise engender the peculiarity of the Western character?

Given the nature of the project, it may be a surprise that Henrich aspires to preach humility, not pride. WEIRD people have a bad habit of universalizing from their own particularities. WEIRD people have a bad habit of universalizing from their own particularities. They think everyone thinks the way they do, and some of them (not all, of course) reinforce that assumption by studying themselves. In the run-up to writing the book, Henrich and two colleagues did a literature review of experimental psychology and found that 96 percent of subjects enlisted in the research came from northern Europe, North America, or Australia. About 70 percent of those were American undergraduates. Blinded by this kind of myopia, many Westerners assume that what’s good or bad for them is good or bad for everyone else. -

September 20, 2020

backlash (ch 13, Layzer)

- The title “entrepreneur” means someone whose job it is to make a case for salience on an issue. What is the difference between a lobbyist and an entrepreneur?

2. This quote:

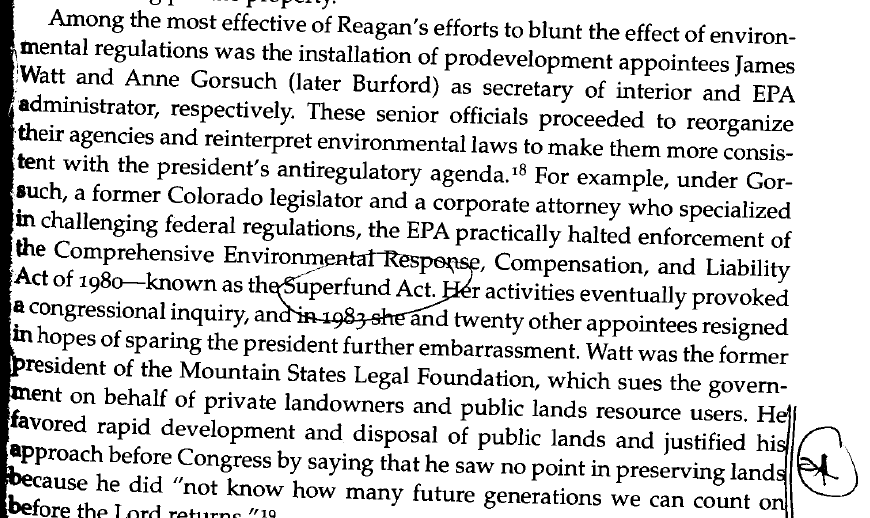

Backlash against the 1970s’ environmentalists’ “honeymoon” with the institution of government regulation began in earnest in the 1980s, under mr cowboy, neoliberal extraordinaire Ronald Reagan and his anti-gov’t platform, supported industry.

The chapter details all the ways a legislator might be covert about the consequence, and use coded language in their arguments, or bury unpopular environmental rollbacks as riders in bills.

(more…) -

September 20, 2020

tackling pollution (chapter 2, Layzer)

Reframing

Change the script in policymaking.

As political scientists Frank Baumgartner and Bryan Jones observe, “[If] disadvantaged policy entrepreneurs are successful in convincing others that their view of an issue is more accurate than the views of their opponents, they may achieve rapid success in altering public policy arrangements, even if these arrangements have been in place for decades.”

(more…)

…if redefining a problem raises its salience-as manifested by widespread public activism, intense and favorable media coverage, and marked shifts in public opinion polls-politicians respond. -

September 14, 2020

evironmental law, overview questions (chapter 1, Layzer)

I’m in a tutorial with John Hultgren at Bennington College, hoping to get some background and working knowledge of how environmental policy works (and seems like it isn’t working).

I started with the introductory chapter from Judith Layzer’s 2002 book, The Environmental Case: Translating Views into Policy (updated in 2015).

Layzer emphasized the use of language that signals values, and values undergird all arguments, along with issues that seem salient enough to be worth any policymaker’s time. Although salience is the result of language (text, visuality) spread widely enough to be significant.

(more…) -

December 11, 2018

Oceans Like Us reading list

Tags:Toxic Progeny, Heather Davis

Becoming Mineral, Una Chaudhuri

How Forests Think, Eduardo Kohn

Anthrobscene, Jussi Parikka

Geontologies, Elizabeth Povinelli

Exposed:

Environmental Politics & Pleasures in Post-Human Times, Stacy AlaimoAlien Oceans, Stefan Helmreich

Mel Y Chen

(video keynote from Future Genders conference here) -

-

August 31, 2018

Toxic Progeny

Breakdown and discussion on Heather Davis’ article Toxic Progeny.

… the whole world can be plasticized, and even life itself.

–Roland Barthes, MythologiesA cod swallowed a dildo. What did it birth? Is it done birthing? Did it die from that encounter?

-

August 26, 2018

On Blue and Sea Colors

Tags:Some excerpts from Brain Pickings’ 200 Years of Blue.

Rebecca Solnit, A Field Guide to Getting Lost:

The world is blue at its edges and in its depths. This blue is the light that got lost. Light at the blue end of the spectrum does not travel the whole distance from the sun to us. It disperses among the molecules of the air, it scatters in water. Water is colorless, shallow water appears to be the color of whatever lies underneath it, but deep water is full of this scattered light, the purer the water the deeper the blue. The sky is blue for the same reason, but the blue at the horizon, the blue of land that seems to be dissolving into the sky, is a deeper, dreamier, melancholy blue, the blue at the farthest reaches of the places where you see for miles, the blue of distance. This light that does not touch us, does not travel the whole distance, the light that gets lost, gives us the beauty of the world, so much of which is in the color blue.

For many years, I have been moved by the blue at the far edge of what can be seen, that color of horizons, of remote mountain ranges, of anything far away. The color of that distance is the color of an emotion, the color of solitude and of desire, the color of there seen from here, the color of where you are not. And the color of where you can never go. For the blue is not in the place those miles away at the horizon, but in the atmospheric distance between you and the mountains. “Longing,” says the poet Robert Hass, “because desire is full of endless distances.” Blue is the color of longing for the distances you never arrive in, for the blue world.

We treat desire as a problem to be solved, address what desire is for and focus on that something and how to acquire it rather than on the nature and the sensation of desire, though often it is the distance between us and the object of desire that fills the space in between with the blue of longing. I wonder sometimes whether with a slight adjustment of perspective it could be cherished as a sensation on its own terms, since it is as inherent to the human condition as blue is to distance? If you can look across the distance without wanting to close it up, if you can own your longing in the same way that you own the beauty of that blue that can never be possessed? For something of this longing will, like the blue of distance, only be relocated, not assuaged, by acquisition and arrival, just as the mountains cease to be blue when you arrive among them and the blue instead tints the next beyond. Somewhere in this is the mystery of why tragedies are more beautiful than comedies and why we take a huge pleasure in the sadness of certain songs and stories. Something is always far away.

Also from Brain Pickings:

Rachel Carson, The Sea Around Us:

To the human senses, the most obvious patterning of the surface waters is indicated by color. The deep blue water of the open sea far from land is the color of emptiness and barrenness; the green water of the coastal areas, with all its varying hues, is the color of life. The sea is blue because the sunlight is reflected back to our eyes from the water molecules or from very minute particles suspended in the sea. In the journey of the light rays into deep water all the red rays and most of the yellow rays of the spectrum have been absorbed, so when the light returns to our eyes it is chiefly the cool blue rays that we see. Where the water is rich in plankton, it loses the glassy transparency that permits this deep penetration of the light rays. The yellow and brown and green hues of the coastal waters are derived from the minute algae and other microorganisms so abundant there. Seasonal abundance of certain forms containing reddish or brown pigments may cause the “red water” known from ancient times in many parts of the world, and so common is this condition in some enclosed seas that they owe their names to it — the Red Sea and the Vermilion Sea are examples.

The unrelieved darkness of the deep waters has produced weird and incredible modifications of the abyssal fauna. It is a blackness so divorced from the world of the sunlight that probably only the few men who have seen it with their own eyes can visualize it. We know that light fades out rapidly with descent below the surface. The red rays are gone at the end of the first 200 or 300 feet, and with them all the orange and yellow warmth of the sun. Then the greens fade out, and at 1000 feet only a deep, dark, brilliant blue is left. In very clear waters the violet rays of the spectrum may penetrate another thousand feet. Beyond this is only the blackness of the deep sea.

-